We're surfers first

Wine writer and surfer Chris Howard reflects on South Africa's surf–wine culture. Above, Kommetjie beach, Cape Town. Image by Alan van Gysen courtesy of local winemaker and surfer, Trizanne Barnard.

‘Remember, we’re surfers first!’ proclaims Eben Sadie as we load surfboards and wetsuits in his bakkie (Afrikaans for pickup truck). Coming from one of South Africa’s most venerated winegrowers, this might give pause. But as a lifelong surfer, it’s a sentiment I understand and share. It’s what we Faustian wave-riders tell ourselves within the wrestle of roles and drives that compete for mastery within the arena of the first-person singular.

Over half the winemakers I meet during my week in the Cape of Good Hope turn out to be as passionate about waves as they are about wine. This isn’t surprising considering the southern tip of Africa is blessed in equal measure with world-class terroir and grand-cru surf. This includes, by many estimates, the most perfect wave on the planet – Jeffrey’s Bay. In addition to exploring South Africa’s heritage vineyards, I was fortunate enough to catch some waves with Sadie, his son Xander and winemaker Duncan Savage, gaining insights into the Cape’s fertile surf–wine scene. As explored below, the binding quality of these twin passions is a particular form of alignment between people and place.

Gear in place for the following day, father and son Sadie fire up the braai – South Africa’s tradition of barbecuing and something of a national pastime. Xander had been surfing earlier, returning with a large yellowfin tuna that he bought from a local fisherman for the equivalent of $5. Normally, he would have speared the fish himself, but this day he had been riding waves rather than hunting fish.

Waiting for the crackling wood to reduce to glowing embers, we sip Sadie’s 2021 Palladius, a beguiling blend of 11 Mediterranean white varieties from 17 parcels. Fermented in concrete eggs and clay amphorae and aged in old wooden foudres for a year, the wine is layered with stone and citrus fruit, with a distinct mineral, saline stratum running alongside earthy, lanolin elements and tightly coiled acidity. It’s an almost surreal wine, even more so when Eben says, ‘and this bottle’s been open for three weeks’.

The fish needs more time and Eben opens a 1970 Zonnebloem Stellenbosch Cabernet that is also in remarkably good condition, the bottle finishing without a speck of sediment. Finally, with braaied tuna, we drink Leflaive Bourgogne Blanc 2018, which, despite the suboptimal vintage, drinks beautifully. We chat until midnight over a drop of Remy Martin Louis XIII and set our alarms for 5 am.

The Sadies live well on their off-grid Swartland farm, though it is all based on hard work, drive and intelligence. Eben is a first-generation winemaker who was drawn to agriculture first and viticulture second. A key protagonist of the ‘Swartland Revolution’, he’s been at the top of the game for the past two decades. Always looking towards the horizon, he’s been planting esoteric yet carefully considered varieties for tomorrow’s sun, including Tinta Amarela, Agiorgitiko, Viura and many others that may require breaking out Wine Grapes. Yet Sadie’s a man of many interests and passions, including green architecture, ecology and, most of all, wave-riding.

Like the other South African surfer-winemakers I meet, Sadie strives to balance work and the siren call of the ocean. All explain how difficult it is to maintain the surfing lifestyle with the pressures of work, lamenting that they only surf once or twice a week. From my vantage in landlocked Paris, this sounds like a luxury, but I understand. Surfing, like wine, has a way of getting under one’s skin and not letting go. As in the wine world, some base their entire lives around it. South Africa’s surfing winemakers do both and know their good fortune to live in such a wine- and wave-rich region.

The twin passions pair well in other locales, including Chile, Portugal, California, Australia, New Zealand, south-west France and the Basque Country. Yet South Africa wins the prize in my view, the closest competition being Portugal and Western Australia (Margaret River). The surf–wine nexus is so developed in South Africa that they even have an annual Vintners Surf Classic, a friendly competition which has been running for over 20 years.

The waves are generally best in the autumn, right after harvest wraps up, illustrating another form of alignment. South Africa has consistent surf year-round, however, and the wine- and wave-oriented traveller will be rewarded along the entire Western Cape. In fact, there are many world-class spots right on Cape Town’s doorstep. Vintner’s champ Trizanne Barnard pointed out at least 15 on a stunning clifftop drive from her beach house. The wind was up so instead of surfing, we tasted through her ocean-inspired wines. This included her Dawn Patrol (surf lingo for an early-morning surf) canned range, which as of 2023 was the official wine of the World Surfing League competition at Jeffrey’s Bay. Professional surfers have traditionally been a beer- and margarita-drinking crowd (among other stimulants), but the tide is turning.

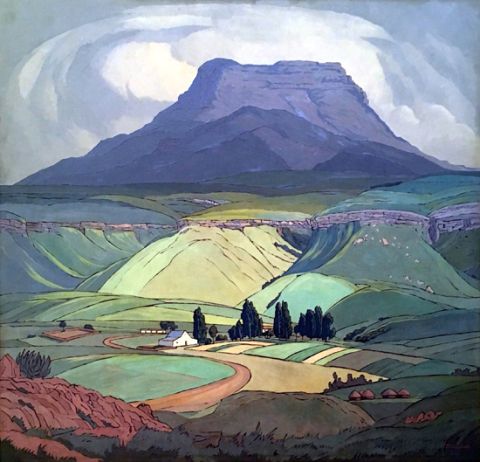

After a stop for coffee and bacon-and-egg sandwiches at Wimpy’s (an SA fast food chain), we spend the morning checking various Swartland surf spots. Swart, I learn, means black in Afrikaans and the region is named after dark foliage that covers the rugged terrain and resembles the skin of the black rhinoceros that used to roam here. Vast, arid plains are framed by the massive, blue mountains seen in the paintings of South Africa’s iconic artist and Eben’s favourite, J H Pierneef, whose permanent exhibition I visited at the excellent Rupert Museum in Stellenbosch. Apparently, when his paintings were first shown in Europe, critics thought Pierneef didn’t know how to mix paint due to the ‘odd’ colour palette. It wasn’t until the advent of colour photography that proved Pierneef was indeed painting South Africa’s unique tones.

After checking 10 or so spots, looking for the optimal conditions, we eventually surf at Elands Bay, a picturesque point break about two hours north of Cape Town. It’s a stunning late-autumn day, the waves are long and groomed, and we surf for six hours, divided by lunch and a short siesta. Having been out of the ocean for six months, I’m not surfing that well, but I catch some waves and I am grateful and content to realise a childhood dream of surfing in Africa, if only for a day. The Sadies and Duncan Savage all surf at high levels. As also expressed by their wines, they appear perfectly attuned to South Africa’s elements.

Savage, although well over six feet tall, moves with graceful economy as he draws clean lines across the waves, and smiles the entire six hours we’re in the icy Atlantic. Following his tenure at Cape Point Vineyards, Savage established his winery in 2011, focusing on precise, terroir-driven wines from 11 vineyards across the Cape. He has a reputation as the hardest-working winemaker in South Africa, yet, like Sadie, he is first and foremost a surfer.

Sunburnt and exhausted, we finish the day with pizza and Savage’s old-vine Cinsault at the art-filled home he shares with his wife, teenage daughters and German shepherd dog. On the affinities between surfing and wine, Savage reflects:

‘Much like the way wine reflects the terroir of a place, waves are a reflection of the coastline and its bottom contours, also reflecting its place. Going on surf trips with wine mates is combining two of the greatest pleasures in life: surfing great waves throughout the day followed by great bottles in the evening, all being enjoyed with one’s mates!

‘The parallels are not just limited to the terroir analogy. Most people won’t pull the corks on treasured bottles at a party with a hundred people smashing the wines out of plastic cups. But sitting around the fire or dinner table with mates enjoying those types of wines and stories creates memories – you know what it’s like. Most of us can remember certain bottles, the people, the weather and the meal with absolute clarity. It’s the same with surfing. Who wants to share great waves with a hundred other people? Surfing cooking waves with a few mates is like nothing else on this planet; the thrill of riding great waves in a pristine setting and watching your mates experiencing the same is incredible. Just like wine, we remember certain sessions, the place, mates, conditions, turns, barrels, etc, the latter even in slow-motion replays on repeat! For most surfers, those stories continue around the fire, but now take that passion and throw in a few cracking bottles of wine among a few surfing winos. The surf stories intertwined in wine discussions … it’s next-level amazing! This is what drives so many of our trips.’

South Africa’s northern neighbour, Angola, had been on Savage’s list for a long time. With a group of surf–wine mates, a trip was finally put together in 2018. ‘Most surfers worry about just getting there’, notes Savage. ‘We worried about getting there and getting 120 bottles of fine wine into the desert …’. His reflections on the trip are worth quoting in full:

‘How many people have sat in the Namib desert after a day of cooking surf drinking wines from around the world out of Riedel stemless glasses around the fire overlooking the Atlantic? On that trip, the top white was Grange des Pères Blanc 2013 and the best red was Penfolds Bin 407 1995. So many were great wines and most tasted blind, with Adi Badenhorst as our resident chef, what more could we have asked for? We trucked the wines up to Windhoek in Namibia, where we collected them after flying in and collecting our 4x4s. These were then smuggled across the border under wetsuits, surfboards and some lesser items like food and water. It’s all about the spirit of such a trip, what in Afrikaans we call “gees”.’

I ask Savage about his Cinsault named Follow the Line, its minimalist label showing a single telephone pole and power line. Considering how both surfing and winegrowing involve following lines, whether they be swells, coasts, vineyards or taste trajectories, I assume there’s a deeper meaning. ‘Actually’, says Savage, ‘the name came from trying to find this old Cinsault vineyard in Darling I’d heard about. I kept getting lost down these dirt roads and having to ring the old farmer to ask where it was. After about five calls he’s getting annoyed and tells me very slowly, “Duncan, follow the line”. The power line, that is, which finally led me to the vineyard.’

Despite this literal meaning, I’m remembering Savage’s surfing earlier that day, the clean lines he drew with his surfboard across the wave faces at Elands Bay, and I can’t help thinking there is more to the notion of ‘following the line’. It brought to mind a surf–wine analogy made by the elder Sadie:

‘Wine needs to transport the soil to the bottle just as the rail of the surfboard needs to transport the surfer through the line in the waves. In the old days, the classic old surfers always spoke about taking the line in the wave and the line of the rail of the board. Most youngsters have no idea what these guys refer to because they’ve all grown up surfing thrusters [short, three-fin surfboards]. When you surf an old-school, single-fin surfboard, you soon learn that there truly is only one line in the wave where the board sits effortlessly and one point from which it turns perfectly. With thrusters, you surf where you want and how you want, regardless of the shape of the wave. So, too, with modern, globalised winemaking. It’s wine that has very little regard for the soil or climate.’

Forms of alignment

What Sadie points to is a form of alignment that experienced surfers and winegrowers share. The basis of alignment is a heightened power of environmental perception, which we can call attunement. Being attuned means noticing how vines growing on sunny, north-facing slopes in decomposed granite soils take different forms than those growing on shady south-facing slopes in sandy loam, and how these forms can be expressed in the resulting wine. What terroir is to seasoned winegrowers is similar to what particular coastlines are to surfers, who similarly become masters in the art of noticing. As the Pulitzer Prize-winning writer and lifelong surfer William Finnegan observes in his memoir, Barbarian Days: ‘The close, painstaking study of a tiny patch of coast, every eddy and angle, even down to individual rocks, and in every combination of tide and wind and swell – a longitudinal study, through season after season – is the basic occupation of surfers at their local break.’

Attunement is thus a way of understanding how elements interact in specific environments. It’s a state of being finely tuned or sensitive to the dynamics of a particular context, whether a vineyard, coastline, forest or city. In a sense, attunement is about stretching out the concept of communication.

Communication is a broad concept that mostly brings language to mind, whereas attunement is more embodied and attentive to form. Winegrowing is a form of attunement in which the bodies of vignerons and those of vines align, if just a little bit. Surfers experience a similar form of alignment when they navigate the currents, rocks and kelp to eventually dance across moving walls of water. The artistry of both surfing and winegrowing thus lie in the creative interaction between people and environments that are always bigger and stronger than them. Both reveal the world by opening up and concentrating the earth’s vitality, though unlike a static work of art, the body is a full participant in a moving medium. Hence, attunement is as much about time as place.

Surfers paddle out and wait to catch waves that are born from storms that have travelled across the ocean. The act of surfing takes place at the moment when the summation of that oceanic energy concludes in the form of a breaking wave – the climax of a long journey. This is what makes surfing utterly unique. In a way, winegrowing follows a similar temporality. The vigneron waits, watches and harvests grapes when they’ve reached the height of their vinous potential. If picked too early, too late or misinterpreted in the winery, the opportunity is missed; the wine will be lacking, the wave gone unridden. Both surfing and winegrowing thus point to what the ancient Greeks called kairos – acting at the right, critical or opportune moment.

But if missed, there will be other seasons and sessions. Surfers and winemakers are utopians, always searching for the perfect wine and wave, knowing that even if tasted or ridden, the thirst will remain. In a world where everything flows, one’s ephemeral sense of alignment – whether riding waves or making wine – becomes an end in itself. The important thing is to follow the lines along which myriad things form, persist and transform.

Wines of alignment

Recommended wines by South Africa’s surfing winegrowers

Trizanne Signature Wines, Seascape Series Chardonnay 2020 Lower Duivenhoks River 12%

Made by avid surfer Trizanne Barnard, this is an elegant Chardonnay from the Cape South Coast region. Half whole-bunch pressed, half crushed to barrel, and ambient-yeast fermented sans malolactic to preserve the natural acidity, it’s structured by bright acidity and river-stone minerality, striking a fine balance between poise and punch. The oak influence (20% new French) is impressively subtle, thanks to the barrels being ceramically toasted versus flame-charred. The ocean-inspired bottle art speaks to the surfer-winemaker's twin passions.

Trizanne Signature Wines, TSW Reserve Sémillon-Sauvignon Reserve X 2017 Elim 13%

Grown in the cool Elim region at the southernmost tip of Africa, this ocean-inflected blend of Sémillon (52%) and Sauvignon Blanc (48%) is fresh, flinty and focused. Lemon-green in the glass, with tangy, concentrated flavours of mirabelle plum, grapefruit, sea-salt-cured lemon and beeswax. Clean acid lines weave through a bony, mineral texture. Matured for 11 months in old, ceramic-toasted 500-litre barrels. Drink with fresh shellfish.

Trizanne Signature Wines, TSW Reserve Syrah 2018 Elim 13%

While the cool Elim area is predominantly great white territory (grapes and sharks), this is a fine example of coastal Syrah from the Cape. Pure and precise, with delicate white pepper, red plum, violet petal and Earl Grey tea notes unfolding across polished tannins and gentle acidity. Destemmed grapes spent four weeks on skins in open-top fermenters, then it was basket-pressed to old oak vessels (225-, 300- and 500-litre) and left 10–11 months before blending.

Sadie Family Wines, Signature Series Pofadder 2021 Swartland 13%

Like Duncan Savage surfing down the line, the wine has a big frame but is graceful and athletic. Translucent ruby, it offers a high-toned melange of cherry, plum, cranberry, pomegranate and ripe strawberry flavours dancing with rose and violet petals, earthy elements and hints of Chinese spices. Great purity and linearity, soft acidity and hidden tannins despite whole-bunch pressing. Versatile, with ageing potential.

Sadie Family Wines, Signature Series Columella 2021

The Family’s flagship red. Syrah plays the leading role, supported by Mourvèdre, Grenache, Carignan and several other Mediterranean varieties from nine Swartland sites. The batches spent two years in barrel (10% new) and old foudres before an act of blending wizardry commenced. Deep ruby, evoking bright red berries and pomegranate crushed on a wet gravel road, perhaps run over by Sadie as he heads for a morning surf. Tremendously fresh, with a seamless, satin texture. Lifted aromas of spicy herbs, violets and iodine counterbalance deeper, darker layers of graphite, black olive and cigar box. Young, enchanting, full of promise.

Sadie Family Wines, Old Vine Series Skurfberg 2020 Citrusdal Mountain 13.5%

From a high-elevation Swartland vineyard on Citrusdal Mountain, this has deep, concentrated varietal Chenin aromas and flavours of green apple, pear skin, quince and lanolin. From a warm vintage that was harvested slightly earlier than usual, it shows great freshness and drive, with firm tannins, nervy acidity and deep mineral layers. Already enjoyable but will reward patience.

Savage Wines, Savage White 2021 Western Cape 13.8%

A blend of Sauvignon Blanc (69%) and Sémillon (31%) from trellised and bush vines around the Western Cape. Rich and expressive aromas of grapefruit, lemon curd, white peach, pineapple, bush honey and chamomile lead into a lush sweep of dense fruit floating along tangy, mouth-watering acids. The complexity and frictionless balance was achieved through whole-bunch pressing and oxidative handling of the must, followed by a natural fermentation and the Sémillon portion going through full malolactic. Ten months in oak (20% new) lends an alluring lick of candied tangerines, vanilla bean and waxy minerality on the finish. Drinking well now and over the next 8–10+ years.

Savage Wines, Follow the Line 2021 Darling 13.1%

Cinsault (93%) sourced from 40-year-old dry-farmed bush vines growing on decomposed granite soil, blended with a touch of Syrah (7%) from the same wind-exposed block, 10 km (6 miles) from the ocean in Darling. Dark ruby with a translucent edge; aromas of crunchy cranberries, fresh strawberries, redcurrants and subtle rose petal and violet. Deep, pronounced red and black berry fruits, morello cherry and wild strawberry with toasty, savoury notes lingering on a spicy, sappy finish. It’s almost opulent, but the tannin structure provides balance and restraint. Very approachable, and great after a winter surf. Drink now or cellar for the next 10–12+ years.

Savage Wines, Thief in the Night 2021 Piekenierskloof 13.6%

Grenache from dry-farmed bush vines grown on sandstone soils, spontaneously fermented with 10–20% whole bunches, then basket-pressed to foudres for 10 months. Pure aromas of rose petals, berry bramble, strawberry preserve and wild thyme. On the palate, tightly coiled acidity binds layers of redcurrant, pomegranate and liquorice with earthy iron elements and savoury herb and salty tide-pool notes. Fresh, with silken tannins, it's an energising, uplifting, seductive wine. Shows why you should put South African Grenache, particularly from Piekenierskloof, on your radar. Drinking well now and over the next decade.

Keermont, Terrasse 2021 Stellenbosch 14%

From the deft hand of surfer-viticulturist-winemaker and all-around nice guy, Alex Starey, this barrel-fermented white is a blend of six varieties grown on hillside terraces in a sublime site between the Stellenbosch and Helderberg mountains. The 2021 is Chenin-led (51%), with Chardonnay adding palate weight, Sauvignon Blanc bringing zing, and drops of Roussanne, Marsanne and Viognier imparting subtle, spicy, aromatic lift. Fermented with ambient yeasts and matured in old 500-litre barrels with some lees contact, minimal filtering and fining. Drink now and over the next 10–12 years.

Keermont, Fleurfontein 2022 Stellenbosch 10.5%

Enchanting dessert wine made from Sauvignon Blanc and named after a spring that runs through Keermont’s mountainside farm and directly below the vineyard from which the grapes are sourced. Autumn-gold in the glass, pronounced pineapple, apricot and desert almond on the nose. Creamy honey over dried fruit, ripe yellow apple and almond cake flavours with a hint of lemongrass. Deeply concentrated, the ample sugar (293.8 g/l) is balanced by vibrant acidity, delivering a long, caramelised finish. This is not a product of noble rot (botrytis), but instead the stem of the grape bunches were pinched at peak ripeness to halt the circulation of fluids from vine to grape, concentrating the juice. A portion of vine-dried Roussanne (15%) adds complexity. Tempting now but will reward cellaring for 10–12+ years.

Reyneke Wines, Reserve White 2021 Stellenbosch 13.1%

A barrel-fermented Sauvignon from Stellenbosch surfer, vigneron and ecologist Johan Reyneke. Zesty lemon-lime and elderflower scents. Pink grapefruit, Tahitian lime, guava and passion-fruit flavours accented by smoky, spicy notes and oyster shell. Firm acidity keeps the weighty mouthful bright and buoyant. Biodynamically grown in the Polkadraai Hills, the grapes were hand-harvested, spontaneously fermented in 300-litre French oak barrels (80% new) and aged on lees for 10 months. Will improve over the next 7–8 years.

Reyneke Wines, Biodynamic Chenin Blanc 2022 Stellenbosch 13.4%

From a certified heritage vineyard (planted 1974) perched atop a hill overlooking the ocean. Varietal scents of Golden Delicious apple, pear and quince, with flavours of white peach, honeysuckle and acacia, along with faint wood smoke and flint. Fresh and lively with tension that makes the wine serious yet approachable. Biodynamically grown and ambient-yeast-fermented in seasoned 300-litre French oak and 2,500-litre foudres, then matured for 10 months on lees. Still young, it will drink well over the next 8–10 years.

Reyneke Wines, Biodynamic Syrah 2019 Stellenbosch 13%

An elegant style, spontaneously fermented in egg- and amphora-shaped concrete tanks and matured in 2,500-litre foudres for 14 months. Deep ruby; lifted aromas of white pepper, red cherry and hints of late-summer lavender; juicy dark fruit, mocha and provençal herbs on a fresh and lively palate structured by chalky tannins and medium acidity. Drink now and over the next 7–8 years.

Images are the author's own unless otherwise credited.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,420 featured articles

- 274,421 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,420 featured articles

- 274,421 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes