What to eat in June and July

A grower's recommendations … (for the UK). Nick took the picture above in Union Square market this week.

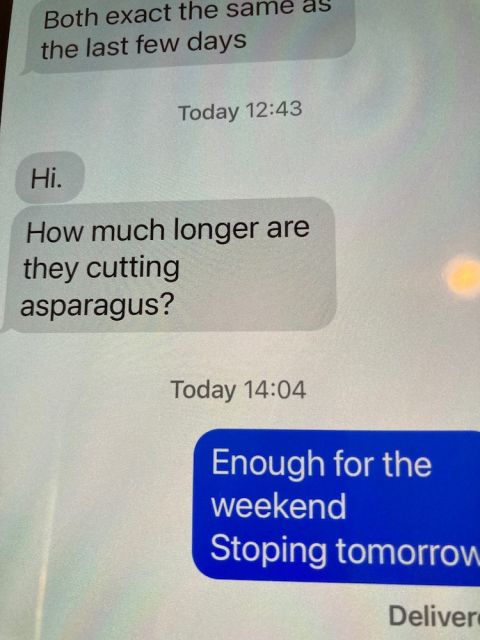

The text exchange below is between Rachel Humphrey, head chef of London’s highly respected Le Gavroche, and her trusted supplier of many fruit and vegetable ingredients. Vernon Mascarenhas of Nature’s Choice (who, inter alia, as their website proudly announces, supply all London’s three-star Michelin restaurants) is the other texter and the message illustrates what currently drives chefs to write the vast majority of today’s restaurant menus.

It is seasonality, seasonality and seasonality.

All today’s chefs are driven to write menus that are based on what is in season, what is coming into season, and when these prize ingredients will slip out of season. Until next year, of course.

The season has just come to an end for rhubarb, which first appeared in its forced variety from the Yorkshire ‘rhubarb triangle’ (the area between Wakefield, Morley and Rothwell) in mid February and has just slipped into, in my particular case, a much-lamented absence. And over last weekend it happened with the last of the British asparagus – it is around Father’s Day every year. As the text exchange shows, the mainly Bulgarian pickers finally finish picking this year’s crop, making sure to leave the crown of the asparagus plant in the ground to begin the very slow process of propagating next year’s crop. And, as we should be entering the prime production period for British strawberries, there comes a warning: the recent absence of any rain combined with the high temperatures and continued sunshine in England recently will have forced many plants to ‘shut down’ (just as vines do in extreme heat) over the past weekend (18–19 June). Let us hope that this is only temporary.

The focus on seasonality is, of course, to be welcomed. It is the culmination of a trend that has been on the rise for the last 40 years but one that has gathered steam thanks predominantly to Brexit and its many unforeseen consequences and, more recently, to certain effects of the pandemic.

It may come as little solace to the many Scottish fishermen who lost the most lucrative outlets for their catch across Europe post-Brexit, but the focus of many chefs across the UK has shifted to their native suppliers, producers and growers. The number of new menus that I am sent which have their focus on British ingredients is staggering. Take, for example, the opening of Goddard & Gibbs, a new British seafood restaurant in what was formerly the Ace Hotel, Shoreditch. Concentrating on British produce is the restaurant’s, and therefore the chef’s, greatest chance of success, it seems to me.

This website does the splendid job of listing by month which ingredients are in season in the UK and makes the very important, and often neglected, point of listing which fish and which meat are in season and when. It is their emphasis on fish that is invariably overlooked. I can still recall getting a lecture from the late William Black, our fish supplier at L’Escargot and about whom we made a Channel 4 programme entitled Mad about Fish, about why eating fish in season was so important. Migration patterns, the fact that fish change their body chemistry during spawning, and the fact that matching seafood demand to seafood availability can shelter the market against a sudden drop in price – these were just three of his, what to me appeared to be, highly persuasive arguments.

The diagrams from the Fishermen’s Mission for June and July show plenty of fish in season during these two months: lobster, plaice, sea bass and mullet in June; mackerel, plaice, monkfish and hake in July. And in season in both months is the megrim sole, cousin to the lemon and Dover soles, almost as tasty and half the price. At The Camberwell Arms I recently enjoyed a megrim sole for two – which allowed me to show off my filleting skills – grilled on a Clay Oven open grill and served with spinach, aïoli and enough roast potatoes for at least six, for a very reasonable £34 for two. It was delicious.

But keeping on top of what is in season requires more than a diligent chef. Changing menus regularly requires not only coordination between the kitchen and the waiting staff who must ensure that all the finished menus are collected and recycled, but it also requires modern printing techniques as well as a committed management.

I recall the days in the 1980s (before in-house printing) when each menu change required: getting the new menu details from the excellent chef, Martin Lam; booking a slot when our general manager Grahame Edwards, he of the delightful handwriting, was free to write out the menu on a blank card (as well as persuading him with the requisite good bottle of wine); taking the finished card round the corner to the printers; collecting and paying for 100 menus at a time; bringing them back to the restaurant; and fixing a date when the new menu could start. The whole process could take more than a week.

Today’s restaurateurs have it much easier thanks to most chefs’ focus on seasonality and the ease of in-house printing. In most restaurants today, menus are printed at 10.30 am and 5 pm for that day’s service, with changes due to dishes selling out being easily accommodated. Printing quantities can be more easily controlled, with yesterday’s menus being physically and easily recycled into today’s.

One other factor has to be taken into consideration and that is the restaurant’s ability to react to the speed of changes in seasonal produce. We recently had dinner with Bruce and Heather Phillips of Vine Hill Ranch in California at the recently opened restaurant in the Twenty Two hotel on Grosvenor Square, where the chefs are Alan Christie and Colin Kelly, who used to cook at Picture restaurant in Fitzrovia. The food, and the wines particularly, were good but lacked any seasonal input or excitement. It was explained to me subsequently that the chefs, rather than being left to their own inspiration, have to cook and show their dishes to a committee for approval. Such is the speed of change in British seasonal produce that by the time the chefs receive the green light, many of the ingredients are on their way out.

This move to seasonality is obviously a very good thing for chefs, restaurateurs and their customers. The only losers, it appears to me – and I heard this comment from the great Simon Hopkinson several years ago – are the food writers for the national newspapers who, for fear of alienating their readers, have to desperately find new and exciting recipes for asparagus, rhubarb and whatever else is in season every year. And have to coordinate this with the necessary photography. Mascarenhas let slip that when Yotam Ottolenghi wrote the food column for The Guardian, the newspaper would take the photographs a year in advance to ensure that they would be available whenever each new ingredient came into season.

Vernon Mascarenhas’ list of what is in season in June/July

From England

- Peas, broad beans, bobby beans, snap peas

- Purple sprouting and tender-stem broccoli

- Kale, cavolo nero, cauliflower

- All salad heads

- Baby leeks, turnips, fennel, coloured carrots and beets

- Wet garlic, spring onions

- Gooseberries for only a four-week season, followed by two weeks of red gooseberries, raspberries, blackberries, blueberries, tayberries, loganberries and currants

- Cherries

From Italy or the south of France

- Stone fruit

From Italy

- Artichokes, borlotti beans and melons

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,417 featured articles

- 274,327 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,417 featured articles

- 274,327 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes