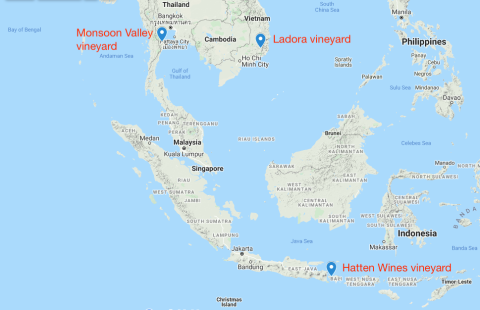

Within a thousand-mile radius of Singapore there are vineyards in three different countries: Thailand, Vietnam and Indonesia (on the island of Bali). At latitudes of 12 degrees north for the first two and eight degrees south for Bali, these are way outside the viticultural Goldilocks zone of 30 to 50 degrees, considered an essential prerequisite for producing good-quality wine according to experts living within those boundaries.

So why does anyone even bother growing wine grapes in tropical climates?

With travel currently outlawed, finding out the answer to that question may take place only within a half-mile radius of my house. Fortunately, my local Vietnamese takeaway restaurant falls within that limit, and the owners were happy, if rather nonplussed, to sell me two bottles of Vietnamese wines from their wine fridge.

As an aside, many wine writers have been musing on whether, in light of COVID-19, our industry should rely less on travel in future. I suppose this article is one way of finding out. Not promising. Despite contacting five people with connections to the Vietnamese wine world, I found my leads mostly went cold (although one informant gave me some tantalising information – see the asterisked comment below). Furthermore, the country’s biggest producer, Ladora Winery, has a website that has been suspended because ‘either the domain has been overused, or the reseller ran out of resources'.

Elsewhere online, however, I found some more promising resources, which have allowed me to investigate the story behind Vietnam’s vines, starting with the general challenges of tropical viticulture, then considering the country’s history of winemaking and examining production techniques, before finally tasting the wines themselves.

Totally tropical taste

Growing grapevines in the tropics has two main implications for quality wine production. The first is that year-round humidity is especially conducive to downy mildew, scourge of vineyards worldwide. The second is that a lack of vine dormancy results in continual production of poor-quality raw material, a situation any sleep-deprived human can sympathise with.

However, that doesn’t mean there aren’t ways that quality can be achieved – and, as Walter points out in his forthcoming articles about pergola training in Italy, traditional assumptions about what is necessary for quality are often unfounded. Perhaps this also applies to latitudes.

For example, to mitigate humidity in Vietnam, elevation can be exploited, such as on the slopes of Ba Vi Mountain near Hanoi, or in the southern highlands region of Da Lat. As for excessive yields, pruning programmes can ensure that grapes receive almost the same 100 days of ripening that is customary in non-tropical climates – although they may still produce a harvest more than once per year.

History of Vietnamese viticulture

In a 2010 report based on his travels in Vietnam, Impressions of Indochina, Levi Hensel explains the history of winemaking in Vietnam. French colonists started the modern industry in the 1940s, with the hilly region of Da Lat preferred for its more temperate climate. Since 1995, international varieties such as Chardonnay and Cabernet Sauvignon were introduced in a bid to improve quality, and presumably to appeal to a more knowledgeable consumer.

There are now around 15 producers, with an annual production of either two or (at least) four million litres per year, according to whether you believe this report or this report. Either way, much of the output is made from hybrid varieties such as Cardinal, or blended with other fruits such as mulberries.

Making wine in Vietnam

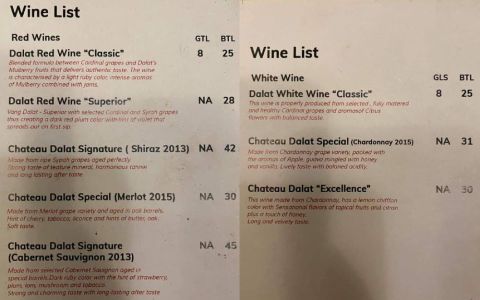

Ladora, the winery that makes the premium range Château Dalat pictured above, as well as the cheaper and more prevalent Vang Dalat, as well as several blended wine products, reveals several of its production secrets online despite the lack of a website. At the top end, much is made of ‘European farming standards’ and the oversight of ‘world-renowned experts’. Yields are 10 to 15 tons per hectare, which sounds reasonable enough – although they achieve this crop level twice every year.

This video shows conventional vine training with vertical shoot positioning and a permanent cordon. Much of the vineyard work looks to be done by hand, including manual harvest of healthy-looking grapes, as shown below, followed by another screengrab revealing somewhat muddy terroir.

At the winery, grapes are loaded into a conveyer, then plunged into the cleaning bath device pictured below before being destemmed and fermented in a large outdoor tank farm.

These techniques may seem industrial – and indeed they are – but that doesn’t make them any less European, as proved by my visit to one of Bordeaux’s largest co-operative cellars five years ago.

Tasting Vietnamese wine

After all that effort, what do the wines taste like? I bought a bottle of Ladora’s non-vintage Excellence Chardonnay and another of their Château Dalat Signature Cabernet Sauvignon from 2013, and the labels and closures were all in good condition.

The Chardonnay was clear and bright, but there the positivity ends, I’m afraid. After a strange nose that was probably acetic influenced, the palate was completely oxidised, with dead fruit and a rank aftertaste. Structurally, the balance was good, and a distinct buttery note was authentic to Chardonnay, if you’re feeling generous, but it was ultimately destined to be drain cleaner.

However, The Cabernet Sauvignon was a very different beast – tamer, friendlier and much more familiar. Despite the bottle age of this 2013, there was plentiful cassis fruit, bright acidity, well-balanced tannin and lingering violet and leather flavours to add complexity on the finish. A neck-tag boasted of the awards this wine has won, and I can see why – it’s plush, modern and entirely drinkable. If it had said Coonawarra on the label, I wouldn't have been surprised*, and the rest of the bottle was disposed of in the usual way via the human digestive system.

(*One local insider suggested that might be exactly what has happened: that Australian wine has been imported in bulk, bottled in Da Lat and passed off as Vietnamese. He told me that all his attempts to visit vineyards in Vietnam have been thwarted, and that efforts by international investors to start making wine in Vietnam were all undone by corruption.)

The why of wine, in Vietnam and elsewhere

Despite the adversities, it is apparently possible to make good wine in Vietnam, but is that fact alone justification enough to do so? To answer that question we should consider why anyone makes wine anywhere.

Here are three main reasons:

- To express a specific terroir

- As an investment, sometimes as a vanity project

- For national and local prestige, including the encouragement of tourism.

The first is the most ostensibly noble, of course, and is the answer given by any self-respecting artisanal winemaker, including plenty of those who more properly fall into the second category, while the third reason could arguably apply to any winery anywhere.

Ladora wine's parent company Ladofoods reveals that it has 'exclusively devoted and invested in the 6 hectare Ladora Winery in Phat Chi – Dalat, Lam Dong. With further investment in a 20 hectare vineyard in Ninh Thuan, Ladora Winery is showcasing its ambition to create high-quality wine that bears a Vietnamese brand name' (my emphasis). Another report states that 'the [Vietnamese] government and Ministry of Tourism have shown a desire to invest more into this industry as wine tourism is beginning to increase.'

But that's not all. Another Ladofoods source explains that 'despite eating a high-calorie menu, French women still have a lower weight index and a more balanced body than other Western women', in a cack-handed reference to the French paradox, whereby diets high in red wine can apparently improve your health.

Who's to say which motivation is more honourable, or which regions should or should not have the privilege of making wine? True, the weight of informed opinion about the best wine in the world mustn't be dismissed, but it wasn't all that long ago that England and Australia were ridiculed for their winemaking ambitions.

On the evidence of the Château Dalat Cabernet Sauvignon I tasted, and assuming it is authentic, Vietnam's vines have just as much reason to exist as any others.