Wine by numbers: viticulture, part one

15 September This is the first in a series we thought would be particularly useful for wine students so we are republishing it free as part of our Throwback Thursday series.

7 September When wine is discussed, figures are often used to illustrate important points. Yield will be quoted in hectolitres per hectare, residual sugar counted by grams per litre, and acidity expressed in power of hydrogen ions.

For the non-chemists or non-statisticians among us, these figures mean little without knowing their context. Hence this mini-series of articles to give the layman an idea of how various measurements used to describe wine compare with each other. This first two articles will concern viticulture, followed by vinification, then on to the finished product.

VITICULTURE, PART ONE

Vineyards are ideal candidates for statistical analysis, especially when they are, as so often, deemed the ultimate key to wine quality. Who can blame wine lovers for trying to quantify the excellence of the world's most precious agricultural land?

Area – introduction

Vineyards are measured either in hectares or acres – and this immediately presents the first of many complications. Different units are used for virtually every factor involved in wine, according to local custom. Unless you are extremely gifted in mental arithmetic, this can make comparison decidedly tricky. Having said that, the conversion factor between hectares and acres is relatively straightforward: 1 ha = 2.47 acres. Using a factor of 2.5 is the commonplace simplified solution.

Area – by country

Area under vine is one of the main measurements of wine production. One of the major sources for these figures is the International Organisation of Vine and Wine, but the OIV includes those grapes grown for non-vinous purposes – that is, for eating, either as fresh grapes or raisins. An alternative source is of course our very own Oxford Companion to Wine, the fourth edition of which was published in 2015. This unveils another problem that afflicts any data project: conflicting sources of information.

Despite that, everyone seems in agreement that the country with the largest area of vineyard is Spain. Rather than listing a top ten, I've selected a few other key countries across the scale to give a sense of perspective. The thing that surprises most people is how big China's area has become, especially when you compare it with more established countries such as Australia. And look at how tiny the UK vineyard area seems by comparison!

| Country | Area under vine (ha) | Source |

| Spain | 1,037,000 | OIV 2015 |

| China | 799,000 | OIV 2015 |

| France | 792,000 | OIV 2015 |

| Australia | 148,500 | OCW4 |

| UK | 2,000 | englishwine.com |

Area – by region

Area – by region

The largest single region of vineyard is the Languedoc, which stretches across virtually all of the southern French coast. At nearly 200,000 ha, this is almost 25% larger than Australia's total vineyard area. At 112,000 ha, Bordeaux is the largest appellation contrôlée area in Europe – twice the size of Rioja and four times the size of Burgundy. Judging the smallest vineyard region is harder since, in some cases, individual regions can be incredibly specific, almost down to the size of individual vineyards – for which, see below.

Area – by vineyard

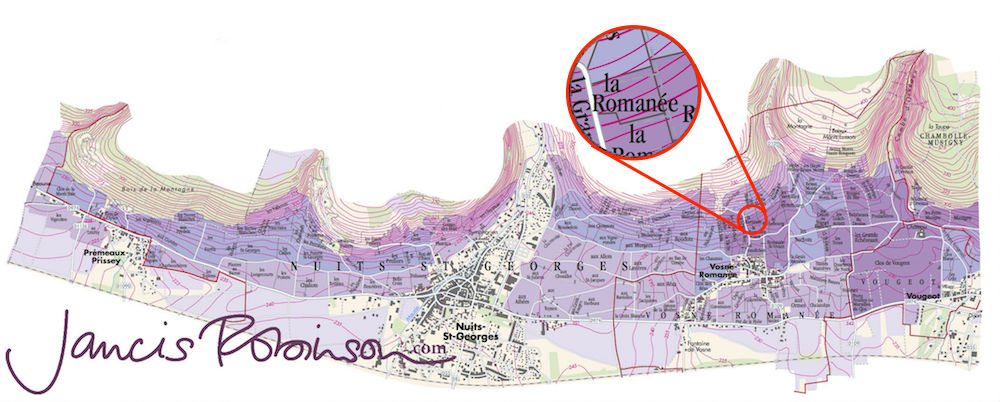

The largest single vineyard is reputed to be in Monterey County, California. Today it amounts to 2,800 hectares but it once totalled 3,441 – in either case, it is much bigger than the combined vineyard area of England today. As for the smallest, Krug's Clos d'Ambonnay must be a contender at 0.68 ha, but perhaps the officially sanctioned answer should credit the smallest appellation in the world, the grand cru of La Romanée in Burgundy, all 0.85 ha of which belong to Domaine du Comte Liger-Belair.

Planting density

Planting density – that is, the number of individual vines in a given area – is often assumed to be an indicator of quality, where the greater the density, the better the fruit. The underlying logic is that closely planted vines have to compete with each other for nutrients and water, forcing them to expand their root structure and produce greater complexity in their fruit. However, there is no proof that this is the case, despite many experiments that have been attempted.

The standard density for traditional European viticulture is 10,000 vines/ha, which gives an inter-vine spacing of one metre by one metre. This is the norm in Bordeaux, Burgundy and Champagne, and it looks something like this, as photographed at Château Ausone in St-Émilion.

At the other end of the scale, Vinho Verde has vineyards with as few as 625 vines per hectare. Further south in Portugal, the sandy vineyards of Colares may been even lower, tending to have large vines sprawling across the sand (see below), sometimes interplanted with apple trees.

Vineyards with densities higher than 10,000 vines/ha certainly exist too. In Bordeaux, Château Croix-Mouton make a cuvée from Merlot planted at 20,000 vines/ha and Domaine Léandre-Chevalier have a site at 33,333 vines/ha, while Domaine de Bellivière in the Loire have an experimental plot of 40,000 vines/ha.

Yield – lowest

Directly related to vine density is one of the most oft-cited pieces of data, yield. Normally expressed in hectolitres per hectare, where a hectolitre equals 100 litres, it gives a measurement of how much wine is produced from a given area. Again, there's a presumption that vineyards yielding less wine should equate to higher quality, because restricting the volume of fruit being grown is supposed to result in greater concentration. The truth is more complicated, and requires some basic mathematics.

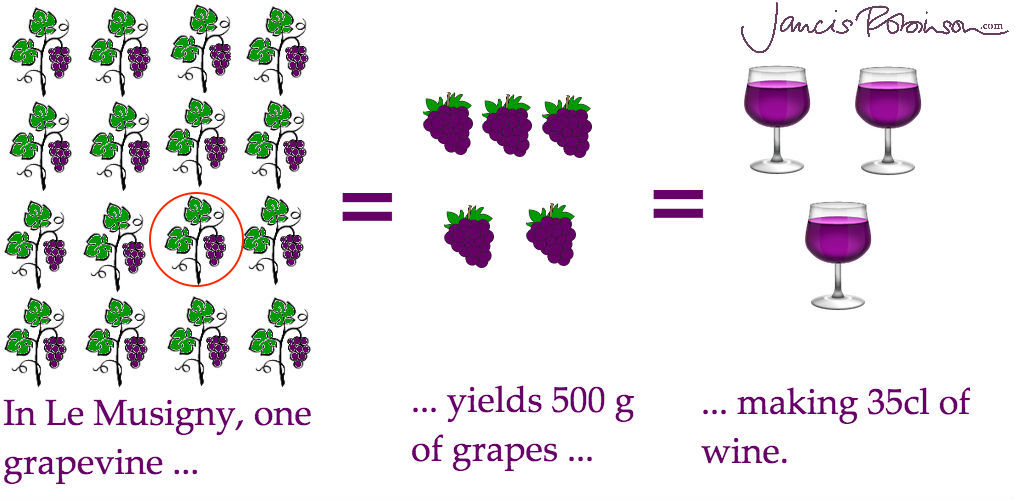

Yield is often enshrined in the appellation laws of traditional areas. One of the lowest is for grand cru burgundy, where a maximum yield of 35 hl/ha is specified for Le Musigny, for example. Importantly, vine density is also specified in these regulations, set at 10,000 vines/ha. With these two facts, we can start to put the figures in context.

Generally speaking, it takes between 130 and 160 kg of grapes to produce 100 litres of wine. For the sake of convenience, let's say the average is 142 kg. So, 1.42 kg of grapes makes one litre of wine. Therefore, if one hectare of Le Musigny yields 3,500 litres, there must be around 5,000 kg of fruit (because 5,000 divided by 1.42 equals 3,500, near enough).

Hence why yield can also be expressed in tonnes per hectare – in this case, it would be 5 t/ha. Because we also know the planting density, we can calculate that each vine yields 0.5 kg of fruit, or approximately 0.35 litres of wine – so, roughly half a bottle per vine.

The lowest of all yields tend to be for nobly rotten sweet wine, whose grapes have shrivelled. In wine-trade folklore, Château d'Yquem produces only one glass of wine per vine. Can we prove this?

The average cited yield for Yquem is 9 hl/ha, which equals 1.2 t/ha of grapes. Planting density isn't known, but its immediate neighbours have 7,000 vines/ha. That would give a yield per vine of 171 grams of fruit, which will produce around 0.12 litres of wine – very close to the standard small glass size of 125 ml. Rare indeed!

Yield – highest

At the other extreme, the Savatiano variety can yield up to 250 hl/ha – 27 times greater than that of Yquem! – and almost certainly at a lower planting density. Of course, with fertilisation and irrigation, yields can be forced ever higher, though such factory farming would inevitably result in dilute, poor-quality fruit from overworked vines. A respectable average seems to be between 40 and 60 hl/ha for quality wines. For much more detail on yields, see the Oxford Companion entry.

Yield – most expensive

Then of course, there is the consideration of the price of the grapes, measured either in US tons or metric tonnes. These two units are different (100 tons = 90.7 tonnes), but close enough to be able to make rough comparisons.

In 2015, the average price for a ton of red wine grapes in California was $783 [pdf], yet, as Alder reported, the price of Cabernet Sauvignon from the legendary To Kalon vineyard could be as much as $50,000 per ton. In South Australia, the overall average price was AU$631 per tonne [pdf], ranging from Colombard from the Riverland at AU$203 per tonne up to Eden Valley Cabernet Sauvignon at AU$2,358 per tonne. Meanwhile, Ferran recently wrote that 90% of Spanish grapes were sold for less than €500 per tonne.

I've converted these figures into GBP, EUR and USD per metric tonne in the below table to allow for a comparison.

| Source | GBP | EUR | USD |

| Riverland Colombard | £116 | €137 | $153 |

| South Australia average | £361 | €426 | $475 |

| Most Spanish grapes, less than | £423 | €500 | €557 |

| California average | £656 | €774 | $863 |

| Eden Valley Cabernet Sauvignon | £1,349 | $1,591 | $1,773 |

| To Kalon Cabernet Sauvignon | £41,919 | €49,462 | $55,126 |

Look out for part two of this series, coming soon, investigating the highest, lowest, oldest and most expensive vineyards in the world.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,430 featured articles

- 274,111 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,430 featured articles

- 274,111 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes