WWC21 – Evangelho, California

8 September 2022 We’re republishing the winning entry to last year’s writing competition with its old-vine theme to remind you to vote for you favourite entries in this year’s competition, as explained here yesterday. The winner, Chris Howard, a social anthropologist who has been working in Wellington, New Zealand, has not yet been able to take up his prize of a trip to investigate The Old Vine Project in South Africa. But he has been offered a position as an economist at the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) in Paris, which he describes enthusiastically as ’the Mecca of wine’, and expects to take this up soon. We’re delighted as it will be much easier to get from there to Cape Town than from New Zealand.

30 August 2021 After first taking us to Chile, Chris Howard's second entry to the writing competition brings us to California. See our WWC21 guide for more old-vine competition entries.

Evangelho - The Vineyard at the End of the World

... the land is much more than its analysis.

John Steinbeck, The Grapes of Wrath

We are in the epoch of simultaneity: we are in the epoch of juxtaposition, the epoch of near and far, of the side-by-side, of the dispersed.

Michel Foucault, Des Espace Autres

In Contra Costa, San Francisco’s ‘opposite coast’, sits one of the United States oldest vineyards. Planted in the 1890s by Azorean immigrants, Evangelho’s roots run deep in an ancient alluvial sandbar where the Sacramento and San Joaquin Rivers converge with the Bay. Surrounded by a power plant, scrap yards, a Burger King and a motel that rents by the hour, the striking juxtapositions and incongruities are a far cry from the romance of Napa and Sonoma. And yet, there is beauty of another kind here, a beauty which perhaps speaks more truthfully to our precarious times.

Under the stewardship of Bedrock Wine Co., Evangelho is registered with the Historic Vineyard Society, a non-profit organisation whose mission is to preserve and rehabilitate old vineyards across California. Morgan Twain-Peterson MW, Bedrock’s owner and winemaker, is a founding member and driving force. Inspired by California’s late 19th and early 20th century viticultural pioneers, Bedrock revolves around some of the Golden State's oldest and most revered vineyards. For Bedrock, the opportunity to make wine from vines that have survived two world wars, Prohibition and an ever-changing marketplace is both a privilege and responsibility. As Morgan puts it, ‘If something has been growing for over 100 years it not only deserves the respect of us humans, but it probably makes some darn good wine too’.

Of the two dozen heritage vineyards Bedrock owns or sources from across northern and central California, viticulturist Jake Neustadt’s suggestion to focus on Evangelho was curious. While the others evoke a rural utopian imaginary, Evangelho first appears like something out of Mad Max or Westworld’s ‘valley beyond’. On winter days, against the backdrop of the power plant, it's as if the vines have somehow survived the apocalypse while everything else has perished. Linger with the disorienting gestalt, however, and the binaries ordering our language and thought begin to blur. Neither utopia or dystopia, Evangelho is better described as what the philosopher Michel Foucault calls a ‘heterotopia’ - an ‘other’ space that disturbs and contradicts our assumed order of things. Understanding these strange spaces requires more than seeing and looking, but what the anthropologist Anna Tsing calls ‘arts of noticing’. ‘Noticing’ implies a subtle but important shift, because to notice something is to realise that it has unsettled your worldview - the way you understand and inhabit the world. If we pay attention, we notice that Evangelho is much more than a vineyard, but a layered microcosm of California history, social struggles, disturbed ecologies and passionate winegrowing.

Evangelho’s Place in the Bay Area

While many of California’s heritage vineyards were planted by Italian immigrants, in Contra Costa it was primarily Portuguese from the Azores archipelago. They came in search of opportunity and upward social mobility following the gold rush of 1849. Grapes were only one of many crops cultivated by these hard working farmers, who also ran sheep and cattle in the area. Historical sources indicate that the Evangelho vineyard was first planted by Manuel Viera, who was born on the Azorean island of Pico in 1854. Having acquired ranchland, Viera began planting the vineyard in the 1890s to diverse varietals, primarily Zinfandel, Mataro/Mourvedre and Carignan. As Jake points out, the 1880s-90s is about as old of vineyards as you can find because the phylloxera epidemic had destroyed most of the world’s vines in the decades prior.

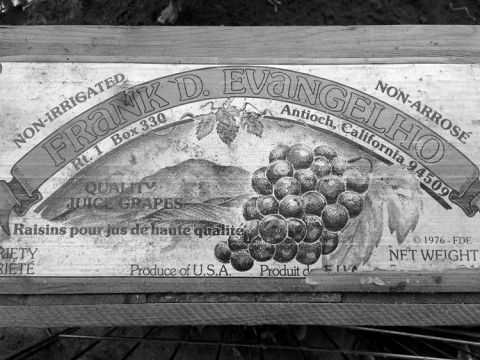

Strategically planted beside a major railway, throughout the twentieth century most of Evangehlo’s grapes were put on boxcars and shipped across the US and Canada for home winemaking or bulk wine. The Vieras sold the 36 acre property to Pacific Gas and Electric (PG&E) in 1952. Manuel Evangelho, a farmhand who had worked for the Vieras since the 1930s, purchased 11 acres and leased the rest from PG&E soon after. His son, Frank Evanghelo, ran the operation until death in 2016. At present, Bedrock owns 30% of the vineyard and leases the remainder from PG&E.

Evangelho and the Terroir of Inequality

Contra Costa is part of California’s great Central Valley, a long strip of land between the Sacramento Delta and the Diablo Range that forms the eastern edge of the San Francisco Bay Area. Evanagelho is located in Antioch, Contra Costa’s oldest city. Prior to a housing boom in the 1980s and 1990s, Antioch and its neighbors Oakley and Pittsburg were small agricultural and industrial towns. The area’s recent transformation follows the same pattern as Southern California’s Inland Empire - new housing developments reflecting new employment geographies in ‘post-suburbia’. A capital for deregulated mortgages, Contra Costa drew hyper-diverse middle- and working-class communities in search of safe streets, decent schools and affordable homeownership on the urban fringe. Tragically, following the 2008 Global Financial Crisis, foreclosure rates in Contra Costa and neighboring counties were higher than San Francisco or Silicon Valley by a factor of more than 100. If the primarily African American and Hispanic families working to build middle-class lives didn’t lose their homes, they experienced catastrophic property losses.

Several years later, San Francisco’s so-called ‘tech boom 2.0’ accelerated the city’s gentrification and total saturation of the property market. A wave of mass evictions, poverty, and homelessness swept from San Francisco to San Jose, profoundly affecting the entire Bay Area. In a deeply racialised reconfiguration, the urban centers have become whiter and more expensive, while more diverse, lower income communities have been pushed to edge cities like Antioch. Despite new ‘affordable’ housing developments, there are pockets of abject poverty and homelessness in Contra Costa.

The housing developments have put increasing pressure on Contra Costa’s few remaining vineyards. Salvador, for example, planted in 1896 and a paragon of old vine Zinfandel was bulldozed in the winter of 2020 for a tract of new homes. The absence of zoning protections for agriculture in Contra Costa means that grapes and other crops go toe-to-toe with ever-increasing Bay Area real estate prices. Yet even before the tech booms, heritage vineyards were an afterthought for the cities of Antioch and Oakley. Over the decades, Frank Evangelho had to bitterly remove thousands of old vines for city projects, some of which never even came to fruition. Paradoxically, Evangelho’s saving grace is not its cult following, but the function it serves for the PG&E power plant. Jake explains that the vineyard exists, and will continue to exist because PG&E wants it to continue serving as a buffer to housing developments. Bedrock leases another nearby vineyard from the Contra Costa Water District, who similarly keeps it as a buffer to the water treatment plant. It’s less about heritage than insurance liabilities, but such is heterotopian life.

In 2018, Kwame Reed, Antioch’s Director of Economic Development came and shot a documentary with Jake about Evangelho as a way to promote Antioch's cultural identity. The video, he tells me, made a big impact in boosting a sense of local pride, with many residents admitting they didn’t know Evangelho was even there.

Ecology, Viticulture and Wine

Evangelho looks like it's planted on a beach because it is. Delhi Sand soil extends a hundred feet down, with some vine roots reaching as deep as 40 feet. Although sand has very little water holding capacity, the root systems are able to draw moisture from the entire soil column since there are no restrictive layers. This allows Evangelho to be dry farmed, as it has from the beginning. Barren as it looks, the sand provides adequate nutrition aside from nitrogen, which is imparted by spring cover crops and composted manure. The vines are spaced 10x10 feet, giving them sufficient room to utilise the soil without competing with one another.

Unlike 95+% of all vineyards, Evangelho is entirely on its own rootstocks. Grafting involves making a massive wound on young vines, cutting both their vascular system and lifespan. More than anything else, Jake insists, minimal violence is the key to vinous longevity. Another aspect of Evangelho’s vitality and the quality of its wines relates to the architecture of its vines. Head trained in the traditional goblet style, each vine unfurls like an umbrella. The arms stretch out and have space, allowing good airflow between the grape clusters. Trellising also allows air circulation, but when vines are trellised, cuts are needed to prevent them from outgrowing their fixtures. Yet every time the wood is cut, it dies back around the desiccation cone. Scar tissue prevents sap from circulating and dead wood builds up over time. Like all organisms, vines need to keep growing and creating new tissue. Pruning also allows diseases to enter the open wounds, another reason that the less violence the better. At Evangelho, Jake says they may cut one arm every couple decades. Despite its 120 years, the vineyard yields a healthy four tons an acre on average. Challenging the assumption that small, low yielding vines are the only way to achieve quality, Jake argues it's not size that matters, but a vines' fruit to leaf ratio.

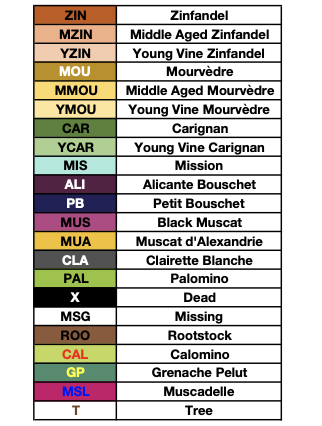

Evangelho wines are traditional California field blends driven by Zinfandel, Mataro and Carignan. Varying amounts of Alicante Bouschet, Grand Noir, Mission, Palomino and even a single, ancient Clairette Blanche vine play supporting roles. Part of the romance of field blending is the potential serendipity that accompanies co-fermenting different grapes, though it's helpful to know what’s what. Hence, in 2017, Bedrock mapped every single vine in the 36-acre vineyard. This was done by walking row-by-row, using graph paper to map the varietals. The handmade map was then converted into an impressive, color-coded spreadsheet of the entire vineyard (see below). When they hit a vine they didn't immediately recognise, ampelography was used to analyse morphological features like leaf shape and cluster characteristics. Only in a few cases were they stumped and sent vine DNA for analysis. ‘If you work with these field blends enough, you can essentially identify Zinfandel, Mourvedre and Carignan from a moving car,’ says Jake.

Besides sulfur, Evangelho is farmed organically, despite severe insect and pest pressure. Given the desolate, industrial setting, this seems like another paradox. But Jake explains how in more biodiverse environments like Sonoma, pests are kept under ecological control via complex food chains. Along with spider mites, mealybugs and rabbits, another ‘pest’ they deal with are recreational dirt bikers that sometimes use the vineyard avenues as tracks and have definitely done some damage to the vines. ‘Another quirk of the area,’ notes Jake.

Evangelho’s wines are as unique and complex as its heterotopian environment. Ethereal, perfumed and Pinot-like compared to the power of Sonoma Zinfandels, they have a cult following but can be polarising. Unsettling binaries like urban/rural, utopian/dystopian, beautiful/ugly, the way into Evangelho is through attentive ‘arts of noticing’. Through noticing, we can perceive latent possibilities even in sites of ruin and seeming desolation, while keeping ourselves from too eagerly celebrating them, because, as we know, these are also sites of struggle, terroirs of inequality. As Jake reflects, ‘It is true that there are ugly aspects to the area surrounding Evangelho… but there is beauty in the amount of diversity in the area.’ Much more than a vineyard, Evangelho is a living monument to California, wine culture and the Anthropocene, which we are all in together.

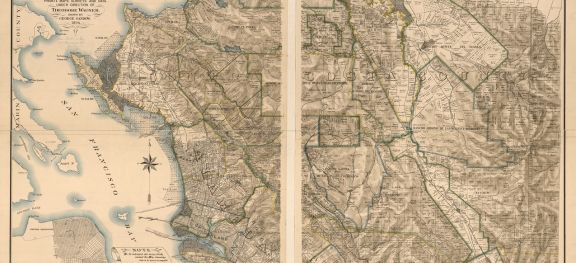

The photos and images are provided by Dr Chris Howard. Credits for all the images, unless otherwise stated, go to Bedrock Wine Co. The main image at the top of the article is an 1894 map showing portions of the East Bay. Image: US Library of Congress.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,416 featured articles

- 275,279 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,416 featured articles

- 275,279 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 48-hour preview of all scheduled articles

- Commercial use of our wine reviews