In the extreme southeast of Turkey, at the conjunction of Turkey, Syria, and Iraq, fields of golden wheat ripple under the scorching sun. Vines older than anyone in the village grow in unkempt bushes interspersed with fruit and almond trees. Shepherds drive the village’s combined herd of cows, sheep, and goats home at sunset. Houses are constructed from volcanic basalt hewn from the earth and church steeples, not minarets, rise above the village. This is the land of the Assyrians - or was once upon a time. Assyrians, an ethnic group indigenous central Asia and the Middle East, have lived and made wine in this corner of Turkey since long before Turkey was Turkey. Now tiny hamlets dot the country’s southeast and sit in a sometimes uneasily surrounded by both Kurdish and Turkish villages.

Located in the Şırnak province, Midin (pictured above) sits at an elevation of 760 meters above sea level and has a hot summer Mediterranean climate. Most precipitation comes in the autumn and winter with a hot growing season with temperatures hovering around 40 C, very dry, with little to no humidity. Constant breezes blow through the fields helping to keep pests and diseases from the vines. Basalt rocks of varying size generously pepper the local landscape, a legacy of the last volcanic eruption here 10,000 years ago. These basalt rocks cover a variety of soil types that make a crazy patchwork of sandy volcanic tufa, terra rossa, and fertile humus. This region looks inhospitable, but it is perfect for grapes.

Formerly a great empire (circa 2500 - 609 BC), the Assyrian population in Turkey has dwindled to only roughly 15,000. They may have lost the empire, but they have not lost their traditions. One of the most significant aspects of their culture is the production of wine. During their heyday, Assyrians oversaw expansive planting of vines, especially around Nineveh in Turkey’s southeast and land for vineyards cost forty times more than land meant for other agricultural products. Wine held great importance especially for religious rites, ceremonies, and feasts. Now largely Christians, Assyrians of old were a polytheistic people and used wine in worship of many of their gods including their national god Ashur; Nanna, god of the moon; Ishtar, goddess of fertility; Ninurta, god of agriculture; and many more. They were renowned for their vines and wines and extended plantings wherever they conquered.

Today, due to pressure from the neighboring conservative Muslim communities and the lack of profitability in maintaining the old vineyards, the practice of these traditions has dwindled. But now, newly established Midin Wine is helping to reinvigorate the tradition and vines. Opened by the Saliba family, one of the village’s oldest families belonging to the Midin village since 1525, Midin Wine is more than a winery, it is a social and agricultural preservation project. The Salibas began the winery with their father’s vineyards. He planted his vines 60 years ago alongside vines a generation older. Previously, the family used the grapes to make some wine at home, but like many of the village’s old vineyards, theirs fell into disuse. Until, that is, the family realized an opportunity to share their culture of wine outside the village and to help lift the village at the same time and reached out to the villagers with a plan.

Midin, the Aramaic version of the Turkish name Öğündükköyü, is a small village with a population of under 400 people from 55 families. Many of these families have small vineyard plots which were harvested for table grapes, molasses, home wine production, sold for pennies per kilo at market, or lay neglected and forgotten and were at risk of being uprooted for more profitable crops. With encouragement from the new, commercial winery, villagers gave up plans to tear out their old vines. Midin Wine pays villagers three times per kilo what they received previously and hopes to increase that price as their wines begin to sell. Thanks to their project, people have returned to the vineyards and are again caring for the vines. Much like they share a single shepherd for their animals, the village has become a small winemaking collective through their contributions to Midin Wine’s production.

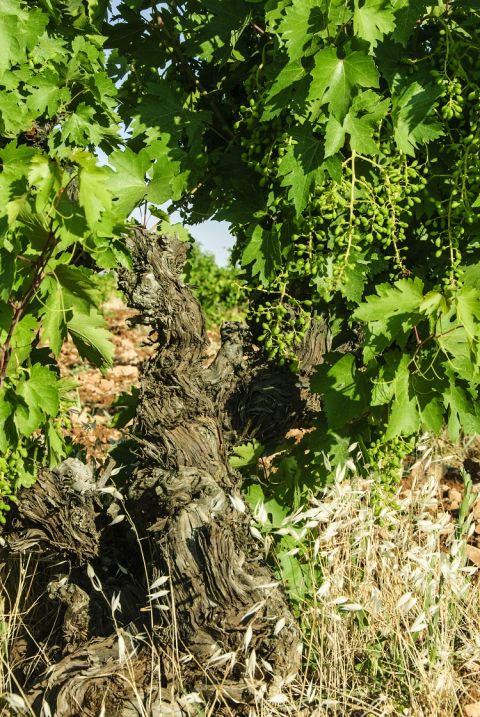

Grapes few have ever heard of like Bilbizeki (see above), Gavdoni, Kerküş, Mazrona, Midin Karası, and Raşe Gurnık flourish mixed together in the vineyards. No one remembers who planted many of these vineyards. Vines range from 60 to 150 years in age and grow untrained and naturally as bushes. Some are so old they have trunks so large that one cannot span them with both hands and have reached almost 6 feet tall. Here, organic is neither trend nor conscious choice; it is simply the way they have always done things. However, to make it official, the winery’s own vines are seeking Ecocert certification and the majority of the villagers’ vineyards have Metekolojik Organik (a local Turkish organic) certification.

In addition to working with the villagers, Midin Wine is planting new vineyards. While these will take decades before they reach ages even close to those of their ancient brother vines, these new plantings will help ensure that these rare grapes are not lost. Together with the agricultural department at Ankara University, the winery’s enologist has begun ampelographic studies to better our understanding of these varieties that grow only in this small area of Turkey.

Through its efforts not only has Midin Wine ensured the preservation and care of vines likely planted by someone’s grandfather’s grandfather, but it has also safeguarded a piece of important cultural history and awakened the locals’ cultural and personal pride in their ancestral village. Their venerable vines now flourish in well-tended patches, their leaves shimmering green under the sun, meander among fruit trees, and border fields of golden wheat, lentils, and chickpeas as they have for generations past.

Photos provided by Andrea Lemieux.