Halloween is the right time of year for blood-curdling horror stories, so this month’s column is all about reduced-alcohol wines. But unlike most horror stories, this one won’t give you nightmares – nor indeed a hangover.

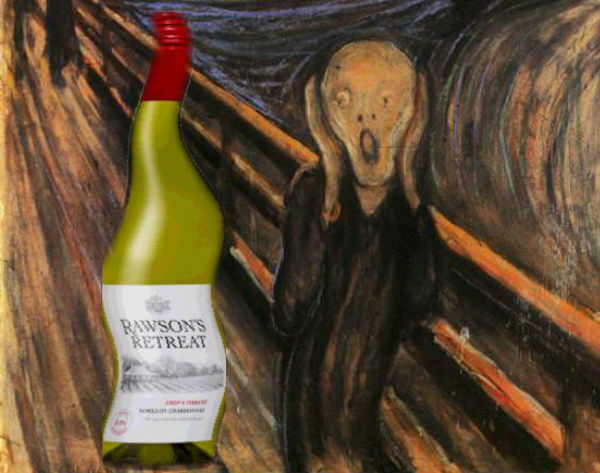

The story unfolds at a local supermarket on a dark and stormy Halloween evening. Our unwitting victim visits the wine aisle where two similar-looking bottles are on sale. They vaguely recognise the name Rawson’s Retreat – once part of the Penfolds stable but now a separate brand. On second glance, they notice that one is a single-varietal Chardonnay, and that the second is a blend of Sémillon and Chardonnay. Casually, they pick the latter – it’s a bit cheaper, after all – and pop it in the trolley.

It isn’t until they get home that they realise with horror that their ‘wine’ ... has got no alcohol in it!

Reduced-alcohol wines are nothing new, of course, but one that is branded so similarly to its full-strength relative certainly is. As a Halloween wine, it’s more Rawson’s Retrick than Retreat, but it illustrates a growing trend that has important implications for the wine industry.

Let’s imagine that you can buy alcohol-free Chablis. It tastes exactly the same as your favourite Chablis but without the alcohol, giving a whole new meaning to the ‘dry white wine’ category. Which would you choose?

Even if the gustatory experience was identical, most wine lovers would surely take the normal version, perhaps because that’s what nature intended, but also because we like the effect of alcohol (see also Is alcohol in wine taboo?). However, for an increasing percentage of consumers, in the UK at least, the non-alcoholic version would be preferred.

According to recent research, the proportion of teetotallers among British 16 to 24 year olds is around 29% – up from 18% ten years ago. Non-alcoholic versions of spirits and beers have now become mainstream and credible, yet the wine equivalent remains elusive. Or does it?

Making wine without alcohol is not easy. Firstly, alcoholic fermentation is essential to convert flavour precursors into the complex aromas that make wine so varied and interesting, and to eat all the sugar. In other words, simply avoiding fermentation is not a solution (it would deliver grape juice). But subsequently removing the alcohol, which accounts for around 12% to 15% of the volume of most wine, also alters the flavour profile and unbalances the structure, as Julia describes in How to make wines a little bit weaker. Plus, it’s an expensive process.

Furthermore, there are legal obstructions. By definition, wine must contain at least 9% alcohol (with certain exceptions) and its alcoholic volume can’t be reduced by more than two percentage points. Using the correct nomenclature for such wines can be torturous – see this article for a horror story of this nature, if you dare.

Yet these obstacles haven’t stopped people trying – which says something about how valuable this sector of the market is perceived to be.

Earlier this year, McGuigan launched a new reduced-alcohol range in Marks & Spencer stores in the UK. Torres’s 0.5% abv Natureo Muscat has been around since at least the 2009 vintage, and while the flavours are authentically grapey, the 27.7 g/l of residual sugar that are a substitute for the lack of alcoholic body are (obviously) much, much sweeter than standard dry white wines. Similarly, there is 45 g/l of sugar in that Rawson’s Retreat Semillon/Chardonnay (and 35 g/l in the red equivalent, made from Cabernet Sauvignon).

Some producers aim for a halfway house. John Forrest in Marlborough is one of the best-known advocates of this style, with his Doctors range of naturally lower-alcohol wines, including a 9.5% Sauvignon Blanc. This is achieved by clever canopy-management techniques in the vineyard rather than any mechanical processing. Domaine La Colombette in the Languedoc use reverse osmosis for their Plume range of 9% wines. Both brands have garnered respectable scores in our tasting-note database.

The pair of 0.5% Rawson’s Retreat wines is significant because it’s the first time a big brand has released a de-alcoholised wine under almost identical packaging. Zero-alcohol Chablis may still be a long way off, but it raises an intriguing thought.

Our perception about quality in wine is entirely arbitrary. We only value dry wines at around 13% alcohol because our palates are accustomed to them; we assume that this is both delicious and objectively correct. But over the years, wine styles are in constant flux. The Falernian wine valued by Romans would be rejected as faulty by most modern palates. More recently, there is rabid disagreement about the quality of heavily oaked, heavily extracted wines, and of minimal-intervention, ‘natural’ wines.

Wine is an entirely acquired taste. But right now, 29% of the UK’s young adults seem unlikely ever to acquire it in its current form. If the trend against alcohol consumption continues, we might all need to reconsider what the ‘correct’ alcohol level is for wine, no matter how horrifying that might seem.