Our 2020 harvest was defined by two challenges – one immediate and the other more wide-ranging, and ultimately far more concerning. Speaking of challenges, the first people to carve vineyards into the mountainsides of the Douro Valley did so with incredible determination, effort and grit. And so it is no surprise that today’s generation of Douro grape farmers and harvest workers, viticulturists and winemakers responded to the challenge of adapting to the COVID-19 restrictions with quiet competence and equanimity. At the same time, they successfully navigated yet another vintage defined by the ever-more-present tests that the climate crisis is throwing at us.

Our reward for growing grapes in such an inaccessible, low-yielding and expensive-to-work region is that we get to spend our days in an area of stunning beauty, we get to work with exceptional people, and we get to produce outstanding wines and ports that have this amazing valley in their DNA.

The impact of coronavirus

As we get only one shot at the vintage, it was essential that we minimised the risk of COVID infections. We implemented a wide-ranging plan to create protective bubbles around the teams. This included testing for every winery worker, many health and safety measures on site, and additional accommodation and canteen facilities to ensure safe levels of social distancing.

This was the first year since we acquired Quinta do Vesúvio in 1989 (and the first year since the winery was built in 1827) that no grapes were foot-trodden in the large granite lagares at the property. Much comment is made about how foot-treading produces superior ports to other methods – and we would agree that this is true in the case of conventional fermentation tanks and plunger mechanisms in the stone lagares which are the techniques of choice in most Douro wineries.

However, in our case, we use modern treading lagares which we designed ourselves in the late 1990s. These consist of silicon pads which actually tread the grapes, simulating the action and temperature of human feet, providing fantastic levels of colour, aroma and flavour extraction. We adopted this technique only once we were convinced that, as proved by rigorous blind tastings, they consistently produced ports as good as – if not better than – those made with foot-treading.

A precocious growing cycle

Although we have weather stations at various quintas in the Douro Superior and Cima Corgo, we typically use Dow’s Quinta do Bomfim at Pinhão in the heart of the region as a barometer for the overall conditions in the Douro. This year, winter and early spring rainfall readings were roughly in line with the average. However, higher-than-average temperatures (with a particularly warm February, at least 2 °C warmer than the 30-year average) caused the vines to emerge from their winter slumber three weeks earlier than usual, with budbreak recorded at Quinta do Bomfim on 3 March. Flowering also started two weeks earlier than normal, beginning on 5 May.

Worrying signs of warming

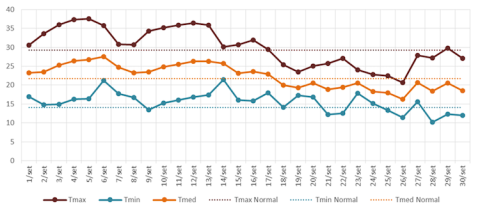

If the overall rainfall levels for 2020 were reassuring (see above), the temperatures were far from it. At Bomfim, every month apart from April was considerably warmer than the 30-year average. The Douro experienced the hottest July on record, 3.5 °C above the average for the region. We also had heatwaves in June, August and September which registered multi-day spikes above the 30-year average maximum temperatures (see charts below). According to IPMA (Instituto Português do Mar e da Atmosfera), the period from January to mid September 2020 was the warmest on record. Globally, climate scientists think 2020 may end up being the hottest year on record (16 of the 17 warmest years since records began in 1850 have been this century).

The good news is that our indigenous varieties are well adapted to hot and dry Douro summers and demonstrate a variety of natural responses to challenging conditions (including reducing berry and bunch sizes and slowing-down maturation). There is also much we can do – and are doing – to adapt to these conditions, from basic techniques around canopy management (and using vineyard layout, altitude and aspect in our favour), to innovations regarding ancestral varieties, climate forecasting software, vineyard robots, and vine water stress studies. However, consistently high temperatures (above 35 °C), are – without a doubt – a problem for the region.

Juggling the picking schedule

Owing to the advanced growing cycle, we were already on track for an early harvest. With virtually no rain in June or July, we were pleased to see 12.6 mm fall at Bomfim on 20 August (generous pre-harvest rainfall is often an important contributor to the best vintage port years in the Douro). Unfortunately, the rain was followed by three waves of high temperatures lasting until mid September. With the heat counteracting the benefit of the water – and faced with the threat of berry dehydration – we began picking white grapes (which were in remarkably good condition) from the 25 August and started harvesting our red grapes in earnest on 1 September.

The summer heatwaves meant that by early September, yields were substantially reduced compared with our July forecasts (up to 40% downwards in some properties). Although a smaller harvest helps with the complicated logistics of grape-picking in the Douro (grapes are predominately picked by hand and with frequent labour shortages), this year’s conditions saw varieties that usually ripen sequentially needing picking at the same time. This was particularly so with the typically late-ripening Touriga Franca, which we decided to pick at the same time as the Touriga Nacional. This is not common. Nevertheless, our experienced vineyard teams adapted exceptionally well, so that the wineries received each variety in the best possible condition.

The Douro is a low-yielding region even in the bumper years, but 2020 has brought us an especially small crop. In some locations in the Douro Superior we were harvesting only 400 g per vine. Quinta dos Malvedos, the primary Graham’s Port estate, averaged just 600 g per vine. Our normal yields per hectare are four times less than many other wine regions. When you factor in the high costs of farming our mountain vineyards, it is no wonder that the only viable and responsible future for the Douro involves selling our fantastic wines and ports at the upper end of the market.

The upside

Fortunately, our reward for navigating these challenges has been that the unsettlingly low yields resulted in some incredibly concentrated and dark wines. My first impressions – confirmed by subsequent tastings – were of particularly promising lagares with balanced Baumés. A comparable harvest is 2009 which was also a very dry and hot year, with low yields that nonetheless delivered small quantities of intense, well-structured wines and ports.

The stand-out has been the Touriga Nacional which has produced wines with excellent structure and good acidity. This is remarkable given the conditions. The Sousão also performed well. The Alicante Bouschet and Touriga Franca were slightly more impacted by the high temperatures, although they did deliver very good quality from more protected slopes and higher elevations. I am pleased with the impact that Sousão and Alicante Bouschet have had on our top ports in recent years, giving us colour, acidity and structure – which is especially important in hot conditions.

The fact that the Douro’s terroir provides such a variety of microclimates is a massive advantage in a year like 2020. It takes a rare constellation of events for quality to be consistently exceptional throughout the region (as was the case for port in 2011, 2016 and 2017), but the investments we have made in our vineyards and wineries over recent decades mean that we have much greater capacity than previous generations to produce small quantities of stunning Douro wines and ports, even in such challenging conditions as were thrown at us this year.

Looking to the future

All of us in the Douro are concerned about climate change. As the Mediterranean climate shifts northwards, we face an increase in average temperatures, lower rainfall levels and more frequent temperature spikes. Although our grape varieties are resilient – and we have been preparing for climate change for many years – more needs to be done to help grape farmers to adapt (including widespread research into vineyard strategies, responsible and sustainable irrigation policies). And to safeguard the future of wine production in the Douro, we need to see a far more ambitious reduction in global CO2 emissions this decade. At Symington, we are measuring our end-to-end carbon footprint and, as members of International Wineries for Climate Action, are signed up to ambitious reduction goals based on the scientific consensus of safe levels of emissions.

Photography project

This year we had a photographer-in-residence working with us at Dow’s Quinta da Senhora da Ribeira in the Douro Superior. You can view Francisco Soares’s digital exhibition, ‘The People Behind the Harvest’, consisting of 45 stunning portraits (each accompanied by a short caption or story), on Instagram: @senhora.da.ribeira_2020. As luck would have it, Soares's time with the pickers coincided with a couple of rainy days in September. Hence these atmospheric but unusual shots.

For a 2020 vintage report on a very different wine region, England and Wales, see here.