It’s a sobering fact that wine consumption, in any form, increases your carbon footprint. But if you’re spending money on wine anyway, you can support and even make an active contribution to carbon-emissions reduction by buying wines from producers who are themselves working towards net zero.

Except that it’s never that simple. A ‘certified carbon neutral’ logo on a bottle may just mean that the company is buying carbon credits to offset their carbon footprint (this logo shows up on some extremely heavy bottles). Other carbon-reduction claims can also be riddled with contradictions and complexity. For example, the construction of an ‘eco-friendly’ winery, dug deep into the earth, may have emitted more greenhouse gases (GHGs) into the atmosphere than the winery will ever save. Solar panels on a cellar roof may not compensate for the carbon emitted by the company’s international flights. Organic and biodynamic farming methods eschew the use of synthetic chemicals but in some cases result in more frequent tractor usage, increasing the carbon footprint. I’ve also found it interesting to note how many organic producers use extremely heavy bottles and ship their wines in polystyrene or swathed in bubble wrap or shrink-wrap – evidence of how blinkered environmental thinking can be. It’s complicated, and greenwashing is as rife in the wine industry as it is anywhere else.

There is, however, a ready-made shortcut for making meaningful, planet-friendly wine-buying decisions, and that comes from a fairly young but disciplined, focused and very fast-growing global organisation – IWCA.

International Wineries for Climate Action (IWCA) was formed in February 2019, when Miguel Torres, fourth generation and president at Familia Torres, and Katie Jackson, second-generation proprietor and senior vice-president of corporate social responsibility at Jackson Family Wines, signed the launch of what has turned out to be a ground-breaking organisation.

At the time, Dr Richard Smart wrote on JancisRobinson.com that ‘there are still too few environmentally aware producers’. But two and a half years later, IWCA membership had swelled to 20 wineries. Last week I sat in a room listening to executive director Charlotte Hey talking about the 145 wineries (representing 48 producers in 12 countries) who are now signed-up members.

That may not sound like an impressive number given that there are estimated to be more than 100,000 wineries in the world. IWCA members represent, therefore, less than 0.14% of wineries and a great deal less of vineyard area. But it is a bigger deal than it sounds. Signing up to IWCA is not like joining a club where you simply pay your membership dues and get free access to the lounge and a badge. It’s more like joining the army.

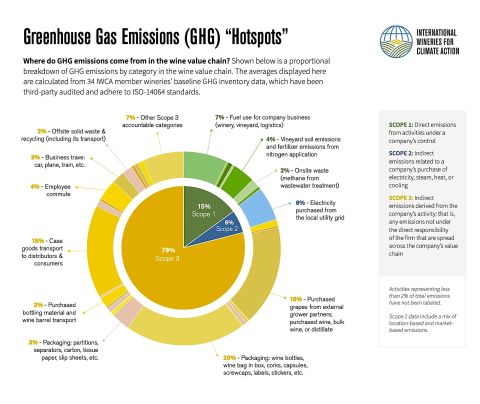

New applicants sign a pledge, which requires them to commit to complete a baseline GHG-emissions inventory (at least scopes 1 and 2) and/or to have a proven plan to complete a baseline scopes 1 to 3 inventory. Applicant members must also agree to complete a third-party audit within one year. This alone is a costly, time-consuming and complex undertaking. And once the focus moves to scope 3 emissions, it becomes pretty hardcore – scope 3 emissions are those over which an organisation has no direct control but has an impact on. For wineries this could be the carbon footprint of glass-bottle production, or the car journeys consumers make to buy wine. To get a feel for how complex and wide-ranging this audit is, take a look at their GHG inventory scopes guidance document. Completing a baseline audit is a financially, logistically and emotionally intensive commitment that requires enormous resources. To become an applicant member is not for softies.

To become a silver member is even tougher, especially for big producers working with growers. The mandatory GHG-emissions inventory (which must be audited by an approved third party) has to cover 90% of the company’s volume of output in the region where the main winery is based. The audits must be undertaken and certified by WRI GHG Protocol and ISO-14604-3 or CDP-accredited auditors. The producer has to have a verifiable plan to reach net zero by 2050 across scopes 1, 2 and 3, and must set intermediate targets for 2030. Gold members must generate at least 20% of all energy consumed by the company on-site, using renewable sources. They also must measurably demonstrate reduction of emissions per litre of wine produced over time.

It’s a seriously rigorous undertaking – this is no greenwashing exercise. The foundational work laid by the GHG inventory flags up the producer’s emissions hotspots – the weak areas that must be worked on in order to maintain membership and progress to the next tier. But it’s also more than a certification boot camp. It’s a working group. The IWCA runs on the principles of collective, collaborative knowledge-sharing and support. They hold regular workshops for members, connect producers to each other and share regular news and topic spotlights to provide members and the public with a rich source of information, inspiration and tools.

What sets IWCA apart from many other environmentally focused certifications is that it is both highly specific and broad. The organisation is aiming for a ‘climate positive’ wine industry – net-zero wine, globally. The way they seek to achieve this is by reducing GHGs – measurable, trackable, auditable. While this might look as if it’s ignoring issues such as chemical pollution, biodiversity loss, ecosystem damage, plastic waste and water waste, a closer look at the audit shows how all these things are intricately connected with carbon (the element of life) underpinning everything. Reduce your use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides (organics) and you’ve reduced scope 1 emissions. Reduce vineyard ploughing (regenerative viticulture) and you’ve reduced scope 1 emissions. Plant trees, hedges and rewild areas (agroforestry and biodiversity) and you’ve reduced scope 1 emissions. Put in solar panels and electric charging points for employees and visitors (BCorp) and you’ve reduced scope 2 emissions. Do spontaneous/vineyard-yeast fermentations and you’ve reduced scope 3 emissions. Reduce your packaging materials (capsules, plastic, wooden boxes, bottle weight) and you’ve reduced scope 3 emissions. These are just a few examples. By reducing carbon emissions, a producer inevitably moves towards environmental and social sustainability, and, over the long term, by reducing inputs and improving resilience, towards financial sustainability as well. In many ways, without explicitly setting out to do so, IWCA is neatly splicing together the aims and principles of many of the major environmental and sustainability certification programmes, without the woolly or siloed thinking behind some of them.

Which brings us back to the beginning: the shortcut that empowers you, the wine lover, to make a positive difference to a planet in crisis. Below, grouped by membership level, are some of the IWCA wineries for whom we have tasting notes. You could see it as a carbon-cutting buying guide, if you will, with the added bonus that a number of the wines these wineries make are affordable and good value.

IWCA Gold members

Alma Carraovejas (Spain)

CVNE (Spain)

Familia Torres (Spain), also La Carbonera

Jackson Family Wines (California, USA) and also Cardinale, Freemark Abbey, Galerie, La Jota Vineyard Co, Lokoya, Mt Brave, Copain, Hartford Family Winery, La Crema, Vérité, Edmeades, Maggy Hawk, Brewer-Clifton, Cambria, Nielson (all California, USA – I haven’t included the Jackson Family wineries in other locations)

Spottswoode (California, USA)

Sula Vineyards (India)

VSPT Wine Group (Chile), including San Pedro, Tarapacá, Viña Leyda, Santa Helena, Graffigna

Viñas Familia Gil (Spain), including Juan Gil, El Nido, Shaya, Lagar da Condesa

Yealands (New Zealand)

IWCA Silver members

A to Z Wineworks (Oregon, USA)

Cakebread (California, USA)

Lanson (Champagne, France)

Château Troplong Mondot (Bordeaux, France)

Cullen Wines (Western Australia)

Domaine Lafage (Roussillon, France)

Famille Perrin (Rhône, France)

Felton Road (New Zealand)

Herdade dos Grous (Portugal)

Herència Altés (Spain) – lightweight bottles (395 g)

Hill-Smith (South Australia)

Miguel Torres (Chile)

Okanagan Crush Pad (Canada)

Piper-Heidsieck and Charles Heidsieck (Champagne) – interesting to note that Piper-Heidsieck uses the lightest bottle in Champagne for more than 70% of their production

Ridge Vineyards (California, USA)

Twomey (California, USA)

Sogrape (Portugal)

St Supéry (California, USA)

Ste Michelle (Washington, USA)

Symington Family Estates (Portugal)

Undurraga (Chile)

Voyager Estate (Western Australia)

IWCA Applicant members

Abadia Retuerta (Spain)

AltoLandon (Spain)

Cedar Creek (Canada)

Domaine Bousquet (Argentina)

Frog’s Leap (California, USA)

Opus One (California, USA)

Ramón Bilbao (Spain)

Tikveš (North Macedonia)

Viña Concha y Toro (Chile)

Coincidentally, and as we reported here, Jancis was recently a recipient of a Torres & Earth award for her work in encouraging sustainability in the wine sector through her reporting in the Financial Times as well as on this site.

All photos have been supplied by IWCA.