Last month, in a car en route to Château de Sérame in the north-eastern corner of the Corbières in the Languedoc, a miracle happened. It started to rain. Proprietor Anne Besse, who was driving, had to turn on windscreen wipers that had lain unused throughout the notoriously torrid 2022 summer. A bright, perfect rainbow appeared to our right over parched vines.

You might argue that Besse needs a series of miracles to achieve her noble aim: to restore her family’s massive, but massively neglected, wine estate and turn it into ‘an innovative and economically viable pioneer of eco-farming and eco-oenology’.

On the drive I learnt that she does start with one major advantage. In 1995 her father, overwhelmed by the responsibility of running Ch de Sérame’s 200 ha (494 acres) of vines, turned them over to the Bordeaux negociants Dourthe/CVBG. During their 20-year tenure, they did the hard work of acquiring valuable organic certification for this vast area of vines – which is one of the largest contiguous wine estates in the Languedoc.

At the point at which the estate reverted to the family in 2015, Besse and her two sisters and brothers were all living in Paris. Inspired by memories of family holidays in the château (they were brought up in nearby Narbonne), they decided to restore it. The next five years were spent exploring the terrain, digging 60 soil pits, selling off the wine in bulk. Only from the 2020 vintage did they take winemaking seriously.

The handsomely illustrated details of the project I was sent in advance of my visit included plans to turn the château into a hotel with eco-lodges attached, opening up the surrounding park to the public, importing sheep to keep the plants between the vines in check, planting tens of thousands of fruit and olive trees, courses in yoga and local cuisine, FabLabs (I had to look these up – they’re small-scale digital workshops) and, of course, thoroughly sustainable packaging. Besse, who has sold her accountancy business in Paris to concentrate on all this and comes down to Lézignan two or three times a month, does not lack ambition.

When we arrived at the property I immediately saw the scale of the work ahead. We parked next to a run of dilapidated sheds, although in the next courtyard there were signs of the new era: a blue food truck and a marquee where they have already started holding events.

The project really got going with the major hire. Aymeric Izard, too tall for the doorways of the old workers’ cottages which house the offices, is used to running a large property. He arrived in January 2020 from Ch d’Aussières, which is Ch Lafite’s Languedoc property, and seems to have brought pretty much all the staff with him. You must be unpopular with the people at Ch Lafite, I observed. ‘A little bit’, he grinned.

But he must be very popular with his new bosses, so calm does he seem about the work ahead. (And my visit was on the day before the 2022 harvest started in earnest, when most wine producers are utterly frazzled.) Izard and Besse took me through the placards along one wall of the courtyard showing maps of the 21 grape varieties planted on the estate, the various soil types and the plans for a new winery.

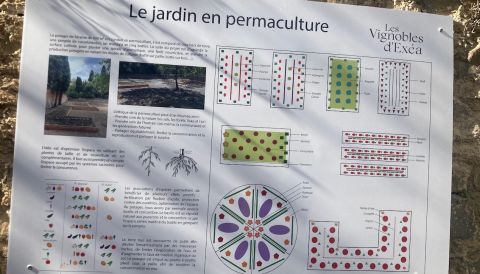

We then set off on a leisurely tour of the château’s seven-hectare (17-acre) park. With its Italianate chapel (a must-have for 19th-century chatelains), grotto, 100-metre (328-ft) balustrade, wide open spaces, Amazonian woodland and one-hectare (2.5 acres) lake, it must have been a magical setting for childhood summers. Besse recalls that the 18-room château would be taken over by up to 15 cousins and their parents. Today, every window is shuttered and the château looks derelict. The terrace in front is an empty stretch of yellowing grass. The chapel’s foundations need repair. The grotto is a storehouse. I felt the same sensation as one does being shown a wreck of a house or flat that has just been acquired by friends who are already seeing it as they want it to be, not as it is. But there was activity in one of their two permaculture vegetable gardens, where we encountered three gardeners sharing a melon. The veg apparently supplies the food truck.

Besse comes from a military family, the d’Exéas, and told me proudly that de Gaulle stayed at the château once, on a tour of redoubts with military connections. But the exploit of which the family is most proud, commemorated on a stone scroll round the coat of arms on the château’s pediment, is an antecedent’s victory over the English during the Hundred Years War, in 1402. ‘In close combat!’, emphasised Besse. ‘Exea Britannos Clauso Certamine Vicit’ (a d’Exéa vanquished the British in close combat) is emblazoned on every carefully designed wine label too. I’m not sure it will be much of a selling point in the UK, but they are only just starting to work on exports (having hired someone from Ch d’Aussières, inevitably, to take charge of them).

They commissioned a team of French designers based in Barcelona who specialise in wine to do the branding and corral their wine production into various ranges – Sources de Sérame (€6.80 in their roadside shop), Terrasses de Sérame, Murmure de Sérame, Blason de Sérame and, top of the range selling for over €18 there, Château de Sérame. They even have a no-added-sulphites vegan wine, the label with special vegan glue, called Orangerie de Sérame.

As well as all of their vineyards in the Corbières, some of them having been planted with such non-Corbières grape varieties as Petit Verdot and Chardonnay by Dourthe to be sold as Pays d’Oc, some of their vineyards constitute the Minervois property Ch d’Argens.

The young Mourvèdre Minervois vineyard, just over the road from their Chardonnay in the Corbières, has been designed to have a hedge running through it to encourage biodiversity. Bats are particularly welcome, as they keep predatory moths under control without recourse to the forsworn pesticides.

It hasn’t been easy. Their second vintage was a disaster with 80% of the crop lost to the exceptional spring frost that devastated the Languedoc in 2021. But Izard is confident about the 2022 vintage just drawing to a close, having started 10 days earlier than usual thanks to Europe’s heatwave. This particular corner of the western Languedoc benefitted from a real downpour at the end of June, and the cover crops in their vineyards helped to retain such moisture as there was in summer 2022. Some of their vineyards also benefit from underground irrigation. It was this and the two lakes and a stream on the property, as well as the soil types, that convinced the d’Exéas to go ahead.

I was shown seven very competently made and beautifully labelled white and pink 2021s as well as six 2020 reds and a 2020 white blend inspired by the oldest vines on the property, 30-year-old Grenache Gris. As so often with Languedoc wines, I found myself favouring some of the simplest wines, the unoaked varietal blends that make up the Sources de Sérame range, as well as the Murmure Syrah rosé and Petit Verdot.

In the reds generally there was strong and rather fascinating evidence of Izard’s background in a Bordeaux-run property. Unlike most Languedoc reds, the tannins were just so smooth. He admitted that he used the Bordeaux (or Ch Lafite?) recipe of very light extraction at the beginning and then tasting twice a day to decide exactly when to move the young red wine off the grape skins.

That they can coax such consistent quality out of the ancient winery says much for the efficiency of Izard, who has a program on his phone to keep track of what’s going on in each of the 80 giant 400-hl (10,567-gallon) concrete vats that are typical of an old-fashioned Languedoc winery. Even though they are busy dividing them in two, even a 200-hl (5,283-gallon) fermentation vat is quite a contrast to the current fashion for fermenting in small lots dictated by each individual parcel of vines. But at least the winery is naturally cool so there’s no need for energy-guzzling air conditioning.

What a contrast there was between the dark, damp interior of the vast winery and the shiny, high tech, stainless steel of the brand-new presses and grape-reception area that had recently been installed just outside the winery according to Izard’s plans. There is EU money available for a small part of this new kit apparently but overall the d’Exéa family plan to invest nearly €10 million in this project, funded by the family’s real-estate business.

I asked the ex-chartered accountant when she expected to start making money at Sérame. ‘Perhaps in five years’, she said, ‘but we have to invest [one million euros] in the distribution network first.’

Once that new sales person gets things in order, wherever you are in the world, look out for a wine label boasting about defeating the Brits. It should be dependable quality and come from an estate that may eventually be worth visiting.

Tasting notes in this tasting article, but don’t expect to find them listed Wine-Searcher.com. Yet.