Do gold wine bottles improve wine quality?

Pick a number between one and 20. Multiply it by your age, then add on a significant year (your wedding, your first child’s birth, your favourite vintage of Barefoot Merlot – whatever). Now double it. Congratulations! You’ve just determined the price you should charge for your PLISC (prestige luxury icon super-cuvée).

Whether that price is by the case or by the bottle or even by the glass, the choice is yours. And feel free to add a few zeros onto the end if you like. In fact, you may as well pick any number you like, because it makes absolutely no difference to the logic of PLISC pricing.

How else would you explain the $1,000 price tag for the new champagne released by Curtis James Jackson III? Perhaps his methodology was to take his stage name and multiply it by two thousand. (He’s 50 Cent. B’boom.)

The strange dichotomy of such arbitrary pricing is that for anyone buying these wines, and who can therefore actually afford them, the exact cost is irrelevant – after all, the ultra-wealthy occupy a world where handbags can cost five figures and even Marmite lids cost £195.

(But everything is relative, of course. I routinely spend £20 on a bottle of wine – an unimaginable indulgence for the 767 million people in the world for whom that would represent two weeks’ budget.)

It is these disparities which make the world of extreme pricing so ghoulishly fascinating.

The most expensive bottle of wine ever sold is still, by my estimate, the notorious Lafite 1787 that cost the equivalent of nearly £300,000 in today’s money, and was subsequently accused of being The Billionaire’s Vinegar.

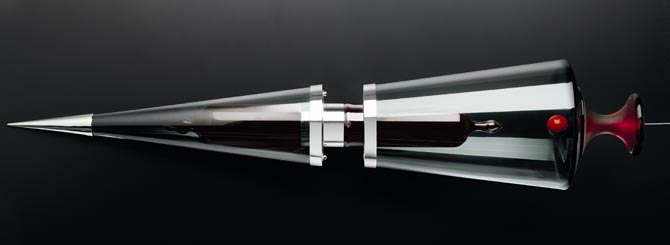

That was sold at auction, whereas the most expensive bottle of wine available via retail was a mere £120,000: the infamous ampoule of Penfolds Block 42 Cabernet Sauvignon 2004. Infamous because it was possible to buy the exact same wine in a normal bottle, and therefore calculate that the ampoule was a cool 105 times more expensive.

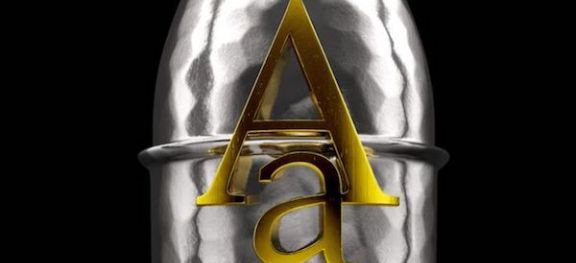

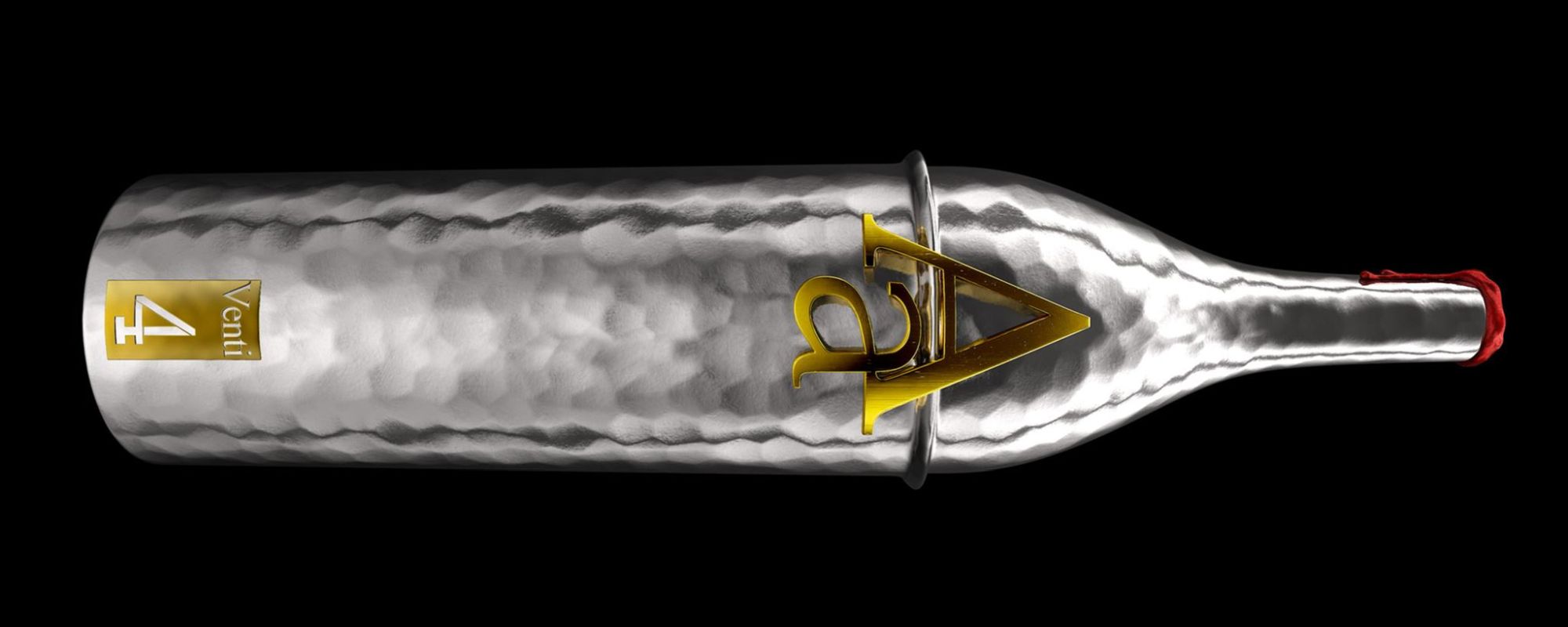

But the latest PLISC to enter the millionaire’s marketplace has solved that problem by creating a unique, 500-bottle cuvée, putting all of it into bottles made of pure gold and silver and charging €25,000 apiece.

In case you missed the vital element(s): yes, the bottles are manufactured from 100% pure gold and silver – yet this is no marketing gimmick, because by using ‘a pure layer of gold interior and pure silver exterior, the design ensures minuscule particles of these precious metals will gradually release into the wine, significantly improving the taste and sensory qualities.’

Such outlandish claims demand scrutiny.

The press release states that ‘Sicilian scientist, Salvatore Valenti, discovers the groundbreaking synergy of gold and silver ions to prevent the oxidation and considerably improve the organoleptic qualities of wine.’ When I asked for clarification, Valenti elaborated that ‘Au and Ag, in [a] synergistic way are able to block in a soft natural way the formation of Sulfidric Acid, one of the main responsible of the bad taste of wine.’

Sulfridic acid is another name for hydrogen sulfide, which can give a foul smell to wines, as the Oxford Companion informs us. This is nothing to do with oxidation, but is certainly a fault when it occurs in bottled wine, albeit a mercifully rare one.

The press release goes on: ‘by blocking the filtration of light, ultraviolet and infrared radiations, a bottle constructed of gold and silver prevents the oxidation and reactions that may occur during the ageing process of wine.’ In other words, because a metal container is opaque, the wine won’t be affected by light – which is undeniably true, although lightstrike is not the same thing as oxidation, and the same results could be achieved by wrapping a glass bottle in aluminium foil.

The Venti4’s real USP is its gradual release of gold and silver (even though the latter is not in physical contact with the wine – something they have overcome via a 'secret' production method) into the wine to positively affect the wine’s flavour. They claim that the improvements will continue in the bottle indefinitely. And the proof has been verified via 'independent' blind tastings ... conducted by the winemakers involved. These two ‘highly respected oenologists [concluded that] compared to the wine aged in the glass bottle, the taste of the wine in the gold and silver bottle stood out clearly every time for its delicacy, for its decisive flavour. The sensorial experience is sublime.’

OH COME ON.

The science behind all this seems to rest on two claims: that opacity obviates lightstrike and that gold molecules reduce the incidence of hydrogen sulphide. The first is self-evident and I don't necessarily dispute the second (although a scientist colleague did, when I asked him about it). But the idea that a 100% pure gold and silver bottle somehow improves a wine’s delicacy and decisiveness is 100% pure gold and silver balls. No matter how robust the methodology of the blind tasting, such terms are entirely subjective.

And even if gold and silver really does improve the sensorial qualities of wine, however you might define them, there is a far more important point to make.

The Venti4 is a luxury product, aimed at the super-wealthy, not at wine experts – as evidenced by sentences such as ‘even the surface of Venti4’s cork is covered with gold; ensuring the bottle provides the perfect environment in which to preserve precious wine’ – yet they are seeking approbation from the wine industry, as you can see from the Twitter feed of the PR agency, which has hundreds of automated messages targeting wine professionals.

The wine inside the Venti4 is described only as: ‘a sublime 2012 super tuscan red wine produced near Greve in Chianti using Sangiovese di Lamole vineyards which are more than eighty years old.’ No details of appellation, winemaking or even producer are provided. (On further enquiry, the appellation is IGT Alta Valle della Greve. I know the producer too, but will spare their blushes.)

Instead there is the spurious claim that ‘for years, within the oenology sector, we have wondered whether we could find a different container able to guarantee a better and longer aging for precious wines. This innovation has finally answered that question.’

The prospect that all fine wines will henceforth be bottled in gold and silver bottles that cost thousands of euros is sheer nonsense – but not because of the sums involved. Outside observers might justifiably berate the world of wine for the money that changes hands for 750 millilitres of liquid. Like so many other luxury goods, there sometimes seems to be no limit to what people will spend.

In fact, the €25,000 price tag of the Venti4 is rather unremarkable compared with countless other luxury products – but the claim to have discovered a way of improving all wine by ageing it in a bottle made from gold and silver, well, that’s just taking the PLISC.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,432 featured articles

- 274,133 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,432 featured articles

- 274,133 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- Commercial use of our Tasting Notes