For Robert Rolls, as for any fine-wine merchant, the initials DRC stand for the world-famous Domaine de la Romanée-Conti in Burgundy. But his younger brother Charles, pictured above, is more likely to associate the initials with the Democratic Republic of Congo, where as a young man he contracted malaria and went on, via a circuitous route, to make a fortune from the experience.

Charles Rolls is far from a medical man. After a stint at Bain, in 1997 he bought into the ailing Plymouth Gin brand and turned it round so that it was snapped up four years later by Absolut vodka, despite gin’s still being, in his words, ‘deeply unfashionable’. (Since then the number of gin brands in the UK has rocketed, from 20 to nearly 2,000.)

While energetically marketing Plymouth Gin he was frustrated by the poor quality of the tonic waters then available. In gin’s most popular iteration, the carefully crafted flavour of his gin was drowned out by the saccharine that dominated the two most common tonics.

So, seeing a gap in the market that was eventually to make him millions, he and adman Tim Warrillow set about creating a premium tonic water that tasted good and whose ingredients were naturally sourced. The quinine crucial to tonic water (and, for many years, to those suffering from malaria) comes from the bark of the cinchona tree. The world’s largest cinchona forests are in eastern Congo, a fact that Rolls remembered from his feverish illness while driving across Africa. They called the tonic water they created in 2004 Fever-Tree.

Rolls gave up an executive role in Fever-Tree in 2014 (‘it’s now too big for an entrepreneur like me’) and has since been looking around for something to do, apart from chairing the Sussex-based Outside In initiative for disadvantaged artists.

Failing to spot such a lucrative gap in the market as premium tonic water and the other fizzy drinks into which Fever-Tree has diversified, he thought about what else he liked drinking. Unlike his brother, he finds red wine too often gives him a headache but he’d found over time that he got on like a house on fire with fino sherry – the pale, dry version. Post Fever-Tree he sniffed around the Andalucian sherry capital Jerez a few times with a view to making and marketing his own but was put off when he found ‘they were all down in the dumps about the sherry industry’ there. Even fino was thoroughly unfashionable, just as gin had been.

He was also wary of the dark, sweet connotations of the word sherry. ‘Everyone thinks of cream, or possibly amontillado.’ He says now he is glad he waited a while before deciding to concentrate on a fino-like table wine that is not as potent as sherry: so a dry wine from sherry vineyards that has a similar yeasty flavour as fino but is only about 12% alcohol rather than being increased to 15% by added alcohol as decreed for fino by the sherry authorities.

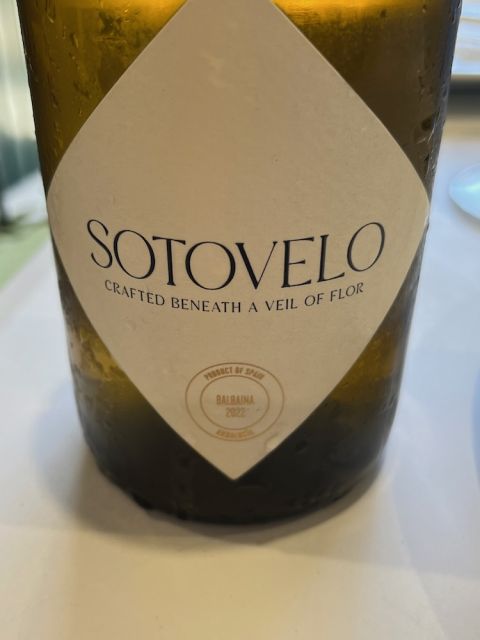

Thus was born Sotovelo (literally ‘beneath the veil’), a reference to the layer of flor yeast that is responsible for fino sherry’s distinctive taste. He recruited as his man on the ground another entrepreneur, of Alsatian/Catalan heritage. Thomas de Wangen imported wine into China for quite a while and got the last pre-COVID flight out of Shanghai in 2019. He had represented González Byass in China and so had spent time in Jerez, where he fell in love with the region. Three years ago he and his Colombian wife Lorna (pictured below) bought 16 ha (40 acres) of sherry vines and a rundown bodega just outside the town and are currently painstakingly restoring it. It is these Palomino Fino vines that supply the raw material both for Sotovelo and for a much smaller amount of fino sherry for Rolls.

I went to take a look at the venture with one of Rolls’s fellow INSEAD business school graduates, Sophia Bergqvist, who has turned her family’s port and Douro table-wine producer Quinta de la Rosa into a highly successful business. It was fascinating to listen to them comparing the fortunes of the two most famous fortified (another word Rolls dislikes) wine regions in the world. ‘I can’t believe how many parallels there are between port and sherry’, observed Bergqvist, who pointed out that at one time port producers such as Croft and Sandeman had operations in Jerez too but have since, like so many once-famous names such as Harveys, withdrawn from sherry.

As long ago as the 1990s those making port in the Douro Valley in northern Portugal saw diminishing interest in port, so they started serious diversification into table wine. Why didn’t something similar happen in Jerez, asked Bergqvist. Why has there been so little producer response to plummeting sherry sales?

And quite apart from the delicious Douro table wines now being made, the Douro Valley and the port city of Oporto at its mouth are now major tourist destinations. Bergqvist herself runs a thriving hotel and restaurant as well as the winery. The rolling chalky hills outside the three sherry towns of Jerez (pictured above), Sanlucar de Barrameda and Puerto de Santa Maria may not be as striking as the steep-sided Douro Valley. They’re now dotted with wind farms; turbines are much more profitable than vines for sherry today. But Jerez is a beautiful, atmospheric, Moorish jewel – yet welcomes a tiny fraction of Oporto’s tourist traffic.

As I wrote last October in Jerez's terroirists and Jerez's unfortified gems, a group of small-scale producers has sprung up in the sherry region making table wine from grapes previous destined for sherry, and very good many of them are. Sotovelo would qualify, although I sensed that Rolls, having tasted market domination, is itching to market his wine independently rather than as a member of a group. This ex management consultant did admit, however, ‘Competition is great – because journalists and bartenders ignore your product until the category exists.’

Another of Rolls’s characteristics according to Bergqvist, who has known him and his family for years, is impatience. Perhaps as a result of this, the first, 2022, vintage of Sotovelo was bottled in May 2023 after only eight months under flor. I suspect rather longer may be needed to make a really distinctive wine. The 2023 vintage is fortunately still maturing under flor in ancient Galician chestnut casks in the de Wangens’ bodega.

The project’s highly experienced Sevillano winemaker Raúl Moreno (pictured above with a specially designed wood-chip container for his imported clay qvevri), a veteran of Marco Pierre White’s London kitchen as well as wineries in Australia, South Africa and the US, showed us just how different the wine in different casks can taste, quite independently of how long it stays there. But Moreno is wary of keeping the wine too long under flor because he thinks it can blur the vineyard character (which is what the new table wine producers generally want to showcase).

De Wangen’s vineyard in the famously cool Balbaina pago is just next door to the first sherry vineyard of another incomer, Peter Sisseck, whose most famous wine is Pingus in Ribera del Duero. Rolls, Bergqvist, de Wangen and I spent a salutary morning at the historic Bodega San Francisco Javier in Jerez, where Sisseck’s finos are maturing (de Wangen and Rolls are pictured below). The difference in pace and ethos was remarkable.

The bodega is owned by sherry grandee Carlos del Rio González-Gordon. Sisseck’s daughter Leonora is now married to González-Gordon’s son. Although based in Madrid, and with his own new venture in Ribera del Duero, Picon del Barroso, Carlete del Rio Oriol, pictured below just outside the bodega, is heavily involved in the cool, dark bodega, whose blackened barrels have been overseen by the same Jerezano capataz, Miguel Calvo, for decades.

In a flower-bedecked courtyard we were brought multiple samples of Sisseck’s maturing fino from his second vineyard in the region, in the Macharnudo pago, bought three years ago. González-Gordon is patiently waiting for his son’s father-in-law to decide when the wine is ready to be bottled. ‘He never thinks it’s the right moment’, González-Gordon, pictured below with Bergqvist, smiled ruefully. ‘And in this business you can’t be motivated by finance. It’s all about quality.’

Rolls, who is still determined to make a little fino as well as to successfully launch his table wine Sotovelo, admits, ‘I realise I have a mountain to climb but I still think fino is a great drink and people will one day realise it.’ Just don’t call it sherry.

Sotovelo 2022 is available from Thorne Wines (£21.75) and Cork & Cask (£23.95).

A few great finos, and some bargains

Waitrose Fino, from Lustau 15%

£9.99 Waitrose

Pedro’s Almacenista Selection Fino, from Sánchez Romate 15%

£11.99 Waitrose

Tesco Finest Fino, from González Byass 15%

£7.25 per half Tesco

San Francisco Javier, Viña Corrales Fino 15%

£34.25 Corney & Barrow

Emilio Hidalgo, La Panesa Fino 15%

£56.75 The Whisky Exchange

González Byass, Tio Pepe Tres Palmas Fino 16%

£53.20 per 50 cl Hedonism

For tasting notes and scores for these and hundreds more finos, see our tasting notes database. For international stockists, see Wine-Searcher.com.