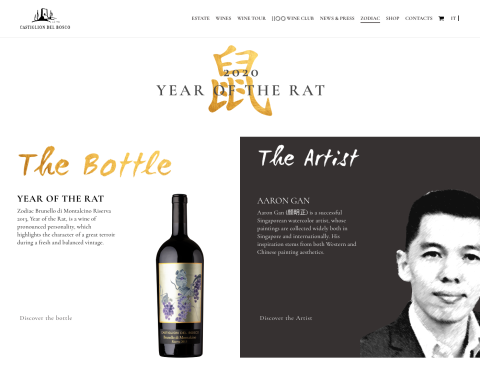

As the year of the rat scampers towards us, a swarm of rodent-themed merchandise has hit the shelves, even including novelty wine labels (pictured). To mark the new year, it seems timely to consider what the future holds for wine in Asia – not just for 2020 but this new decade.

But first, let’s review how wine in Asia changed throughout the 2010s. The decade was kickstarted by the abolition of wine duty in Hong Kong in 2008. Consumption was already on the rise, with China drinking 15.1 million hectolitres (398.9 million gallons) in 2010. By 2018 (the most recent figures available), that had grown by 16.5%, far outstripping the global average increase in wine consumption of 1.4%.

However, it wasn’t plain sailing. After gifting was banned by the Chinese government in 2013 in a crackdown on extravagant spending and bribery, fine-wine sales took a hit, and in the last few years overall wine consumption in China seems to have stalled completely, as trade wars and slowing economic growth take their toll.

Meanwhile, annual per capita consumption in India has doubled, although it still equates to only a spoonful of wine per person, while Hong Kong, Singapore and Japan remain necessarily small markets, albeit with certain strategic advantages.

At the same time, Asian wine production has grown in ambition, especially in China and India. While there is still a long way to go, the emergence of luxury brands such as Long Dai and Ao Yun indicates that some producers (both French in this case) have both the self-belief and the funds to invest in their fine-wine future.

2020 vision

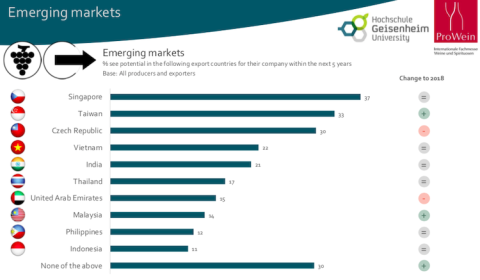

Despite the unpredictable nature of consumption, the wine trade apparently still has its sights set firmly eastwards – and US tariffs on European imports are doing nothing to discourage this. The 2019 ProWein business report surveyed wine businesses around the world. Three of the top four most attractive markets are China, Japan and Hong Kong, while the top two emerging markets are Singapore and Taiwan, as shown in the tables below.

Natalie Wang, founder of the invaluable Asian wine news site Vino Joy News, believes that the perceived riskiness of the US market, where recently imposed 25% tariffs on imported European wine may even rise to 100% on an even wider range of products, means that European producers are especially keen to diversify their export markets. The new Economic Partnership Agreement between Japan and the EU makes that country an attractive target, although she believes growth will be moderate, presumably because it is already so highly developed.

In Singapore, wine editor of epicure magazine June Lee sees younger consumers moving towards ‘trendier drinks like whisky, gin, cocktails, even sake', although she acknowledges that wine festivals (such as the recent Pinot Palooza) ‘are still a good way of bringing an audience to wine, with more lifestyle elements (eg DJ booth) for the younger crowd and highly rated/premium labels for the discerning crowd'.

Meanwhile, prospects in China are looking rather gloomy, with wine consumption falling rapidly. Wang believes that a combination of depreciating currency, trade wars and a slowing economy have led to this consumer cautiousness. She reports that in 2019, ‘over 2,000 bottled-wine importers went bust in the first five months of the year, according to official figures [...] and more are expected to go out of business in 2020'.

Beijing-based Edward Ragg, who became a Master of Wine last year, believes that the rapid increase in wine education means that margins will become less exploitative as consumers become more sophisticated – but that import volumes are unlikely to grow much further. He believes that the opportunity is best for mid-market and premium wines, especially those which are not yet well known in China, whereas Wang thinks that lower-end wines from Chile and Australia will be preferred by importers who are in damage-limitation mode. She also identifies an opportunity for countries such as Moldova or Georgia that may benefit from the One Belt One Road initiative (see this Meininger’s article for more information).

As for domestically produced wine, Ragg thinks that ‘only the very best Chinese premium producers will survive, provided they can rationalise pricing and captivate younger wine drinkers’, although Wang is more optimistic, thanks to improving quality and ‘unfortunate nationalism’ that is being fuelled by the trade war.

Eastern promise?

Asia might not turn out to be the land of golden opportunity that the wine world seemed to be hoping for. Even so, the temptation to target Asia remains strong because there are so few other untapped markets that show a developing wine interest.

However, the prospect of Asian culture changing the fundamental ways in which wine is made and marketed (as I considered in Redefining the culture of wine?) doesn’t seem terribly likely – although that hasn't stopped this inventive Brunello producer from giving it a go.