Britain’s wine merchants are already beating the drum about the 2018 burgundies they will be offering their better-heeled customers next month. (We plan to begin our extensive coverage of the 2018 vintage on 30 December.) I wonder how many of them in their literature will take heed of the name change urged by the official body, the Bureau Interprofessionnel des Vins de Bourgogne: ‘to re-affirm their identity, the region and the producers are reverting back to the original French iteration of the name, Bourgogne’.

In the northern hemisphere it may seem strange to be discussing heatwaves in the depths of winter but please stick with me if you are interested in wine. Summer last year was particularly hot and dry. The first heatwave vintage experienced by the current generation of Burgundian (Bourguignons?) wine producers was 2003, which makes tasting 2003 burgundies today a particularly interesting and relevant exercise.

Although peak temperatures were similarly uncomfortable (over 40 °C/104 °F), and both 2003 and 2018 were summer drought years, there are some differences between the weather patterns of the two growing seasons, particularly in terms of when rain fell. In 2003 most of the rain fell during the winter months whereas spring 2018, right up to June, was notably rainy, so the water table was good and high before temperatures started to soar in 2018.

The 2003 heatwave was quite remarkable. Nights as well as days were staggeringly hot. This was the year when some vignerons were reputed to have taken to their cellars in order to sleep comfortably, and the newspapers were full of reports of elderly Parisians who perished in the heat.

Frost in April had reduced the crop so yields in 2003 were relatively low whereas the 2018 crop in the Côte d’Or was notably generous. The total for Côte d’Or reds in 2018 was 16% higher than the average for the last five years whereas the equivalent figure for the white wine produced on the Côte d’Or, which represents slightly less than one bottle in every three, was a whopping 28%. This at least means that prices for the 2018s should be relatively stable, or rather still expensive but no more expensive than last year.

Another factor that differentiates 2018 from 2003 is that with every year that average temperatures rise, winemakers become more skilled at coping with fruit grown in a heatwave. And, purely observationally, it seems to me that vines appear to be adapting to a hotter climate, with wilting and yellowing leaves being a less immediate symptom of what the French call a canicule.

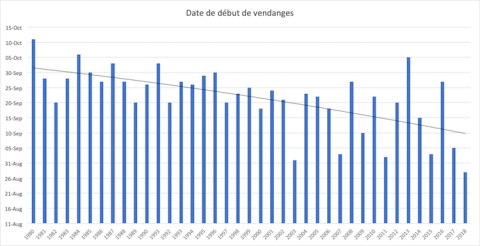

But the most dramatic change has been in harvest dates. Frédéric Mugnier of Chambolle-Musigny has charted the date of the start of harvest from 1980 up to 2018. In 1980 the harvest didn’t start until 11 October but the graph is basically, with a few variations, a downward slope, showing that 2018 was the earliest-picked year, starting on 27 August, but with notably early harvests in 2003, 2007, 2011, 2015 and 2017. Picking grapes in August is no longer unusual and vignerons’ families can no longer rely on long summer holidays.

This seems to us today to be entirely a recent phenomenon but researchers at the Université de Bourgogne have managed to establish the start dates of the grape harvest as far back as 1371. (This alone is surely enough to strengthen any wine lover’s admiration for Bourgogne.) What is remarkable is that they found no fewer than 12 vintages between 1420 and 1719 when their antecedents started picking grapes in August, on the earlier-maturing Côte de Beaune at least. But none between 1720 and 2003. Specialist Burgundy photographer Jon Wyand took this picture of a commemorative plaque in Puligny's Folatières vineyard.

I have been lucky enough recently to taste quite a number of 2003 reds thanks to the latest in my fellow Master of Wine Sarah Marsh’s series of retrospective tastings of mature vintages of burgundy, as well as some whites from two great winemakers Jean-Marie Guffens of Domaine Guffens-Heynen and his négociant business Verget, and Lalou Bize-Leroy, whose recherché home farm is Domaine d’Auvenay.

Sarah Marsh’s selection of 25 2003 reds from superior producers was qualitatively more varied than any she has assembled so far in these vintage reviews. (Some of the grandest bottles are shown above.) Many of the wines tasted as though they still contained some unfermented sugar and almost all of them were marked by rather dry tannins, a typical hallmark of drought-ridden vintages in which grapes are particularly small, with thick skins, and are sometimes shrivelled.

Two of Sarah Marsh’s 2003s were rejected because of TCA, the damp-cardboard-like cork taint compound. Another three were taken off the tasting table because of general mustiness or lack of cleanliness. Some wines were falling apart while one or two of the grands crus were simply sublime.

The finest of these was a Bonnes Mares made by Freddy Mugnier, so I asked him how he chose to cope with this exceptional 2003 vintage. He describes 2003 as a vintage that taught him a great deal. (He returned to the family domaine from a career as a pilot in 1985.) ‘There was every reason to change our usual habits’, he explained by email.

‘In mid August all the oenologists and technicians, influenced by the analyses of the grapes, were advising radical measures: immediate picking, minimal skin contact, cold and fast fermentation, and massive acid additions.

‘But I saw that the grape colours didn’t look ripe. I waited until 1 September by which time the analyses hadn’t changed. Sugars hadn’t risen, acidity hadn’t fallen any further. So I made my wine in my usual way, punching down the cap of grape skins very little (as usual) and adding no acid at all. The big lesson for me was that you shouldn’t be tempted to correct the extremes of a year by winemaking techniques. The risk is that you lose the balance and end up masking the vintage’s character. And what’s the point of that?’

Many less-thoughtful producers added acid in an attempt to compensate for the vintage’s low natural acidity as a result of the extreme heat. They regretted it later when it never seemed to become fully integrated into the wine.

Of the handful of 2003 whites I have tasted recently, it was very obvious that the acidity levels were much lower than usual, but skilled hands can make a great wine – even if it is quite different in character from other vintages.

Such 2018s as I have tasted suggest that winemakers, even in Bourgogne, are no longer scared of blistering hot vintages. Certainly the whites seemed crisp enough, though the reds can be so high in alcohol that they taste very different from traditional norms. I spotted a 15% on the label of a Chanson white 2018 premier cru from Pernand-Vergelesses, a village round the back of the hill of Corton whose disadvantage used to be a lack of ripeness.

Some successful 2003s

You could try finding one of these via Wine-Searcher.com but quantities are so tiny that it is a very long shot indeed.

Whites

Dom d’Auvenay, Grand Cru Chevalier Montrachet

Dom Guffens-Heynen, Pouilly-Fuissé, Premier Jus des Hauts de Vignes

Verget, Chassagne Montrachet, Premier Cru Les Chenevottes Canniculus

Reds

Dom de L’Arlot, Nuits-St-Georges, Premier Cru Clos des Forêts St-Georges

Dom Pierre Damoy, Grand Cru Chambertin-Clos de Bèze

Dom Marquis d’Angerville, Volnay, Premier Cru Clos des Ducs

Dom Michel Lafarge, Volnay, Premier Cru Clos des Chênes

Dom Mugneret-Gibourg, Grand Cru Échezeaux

Dom J F Mugnier, Grand Cru Bonnes Mares

Dom Armand Rousseau, Grand Cru Clos de la Roche

Recent tasting notes on the reds can be found in our tasting notes database. Tasting notes on the whites to follow.