In June of this year, on a trip to Armenia, I sat in the carpark/pallet-storage yard of Wine Works, under a vine-entwined patio in the bright sunlight. With me, pouring wine and chatting non-stop, were Vahe Keushguerian and his daughter Aimee. We were metres from their aesthetically brutal Soviet-factory-conversion winery, modern stainless-steel tanks shining in the hot sun. The table was laden with apricots, green plums, cherries, strawberries, white mulberries, just picked, from nearby. Plates of local cheese and charcuterie alongside freshly made lavash smelled glorious. This feast arrived after a conversation which went:

‘Have you had breakfast?’

‘Yes, thank you!’

‘Are you hungry?’

‘No, thank you, that’s very kind, but I’m fine.’

‘OK, just a small snack, then.’

Six platters of food later, we left satiated, but not without a large paper bag, handed through the car window, bursting with two varieties of cherries as well as a plastic lunchbox full of food. For the road, we were told. Lunch, mind you, was due in 15 minutes. Just down the road.

This is not really the story of the wine I’m writing about, but it gives context.

Keushguerian, who, for years, made wine in Puglia, Tuscany, Australia and California, has the energy of a teenager and a rapier-sharp, restlessly curious intellect. He’s an engineer, a businessman and more than a little cynical. But he is also a dreamer with a passion for culture, particularly that of his homeland and the wider region.

Working with his American-born daughter Aimee, he and his team custom-crush for hopeful start-ups with vineyards but no winemaking facilities. They also make their own wines, driving long hours up perilous mountain roads (I write this with feeling – I’ve been on those roads) to search out abandoned vineyards, and they pay growers several times what they’re usually paid (as most grapes here are destined for brandy production) for their fruit.

Keushguerian believes in the rich tapestry of the winemaking history of the region, but he also believes that the political borders of Armenia are not the wine borders. After all, Armenia was governed by the Persian empire in one guise or another for several centuries. And, he points out, Iran shares with Armenia ‘the privilege of being one of the birthplaces of viticulture’. As Julia mentioned in Digging in Armenia, archaeological research has shown that grape-wine residue was found in wine jars in Hajji Firuz Tepe (an archaeological site in north-western Iran) dating back to 5,400 BCE. This is older than any wine-related archaeological evidence found in Georgia or Armenia.

Today 3.4 million tons of grapes are harvested in Iran, but even though this includes wine-grape varieties, the grapes are sold for the table. Despite Iran’s long history of winemaking, embedded even in its legends, wine has not been legally produced in the country for more than four decades. At the time of the 1979 Islamic Revolution there were nearly 300 wineries in Iran. Today there is none. And it is because of this that Keushguerian decided to make an Iranian wine from indigenous Iranian grapes. ‘Wine was made in Persia for centuries’, he tells me. ‘It’s part of Iran’s culture and heritage. And it’s the worst-kept secret that Iranians still cross the border to Armenia to drink wine! I have wanted to make this wine for years.’

There are around 6,500 ha (16,060 acres) of vineyards in Sardasht County in the province of West Azerbaijan, close to the 44-km (27-mile) border that Armenia shares with Iran. An ancient black wine-grape variety called Rasheh still grows there, thriving on the volcanic soils, in the extreme climate and at the exceptionally high elevations (1,480–1,500 m/ 4,860–4,920 ft) of this mountainous region.

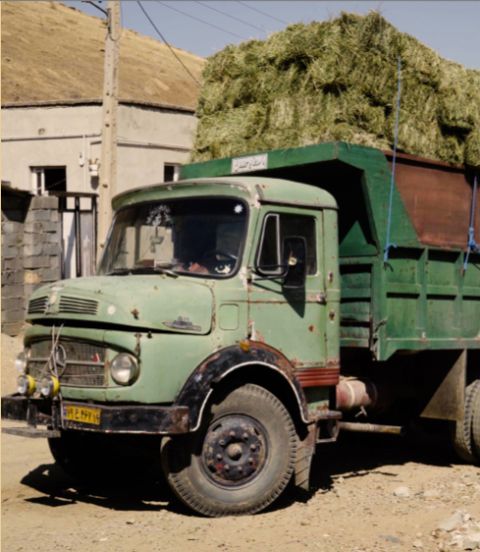

On a scouting mission, Keushguerian describes that ‘what we discovered in the way of vineyards was beautiful. Small patches of vineyards placed high on hills that are mostly accessible by foot only.’ It was a madcap idea, and a genuinely dangerous undertaking, but in 2021 they headed up into the mountains with donkeys and banana crates. They hand-picked Rasheh grapes from old, isolated vineyards of ungrafted bush vines growing on steep slopes. The donkeys brought the crates of grapes back down. They were loaded into ancient, battered trucks, covered with grass bales, and driven several hundred kilometres, across the border, to Yerevan in Armenia.

They filmed the project with a skeleton camera crew. They wanted this to be a historical milestone, and they wanted to capture every moment, Keushguerian tells me. And then he pauses. Laughs wryly. Says, ‘Once this story gets out, there will probably be a price on my head. I will certainly not be welcome in Iran again.’

Forty days of spontaneous fermentation later, the first modern, commercial Iranian wine in more than 40 years was born. They made about 10,000 bottles and named the wine Mòläna (which is a version of the Arabic word mawlana or maulana, meaning religious scholar and teacher) in honour of the 13th-century Persian poet Rumi, who was sometimes referred to as Maulana Rumi. Keushguerian says that the purpose of this project was to rediscover Iran’s vineyards, to learn something about its winemaking legacy, to explore its oenological potential, to understand its terroir. Rumi was teacher, innovator, playful, romantic, and above all, a Persian wine drinker and wine lover.

The wine is as extraordinary as its story. It’s as pale as Pinot Noir, smells of wild strawberries and baharat spices. It’s a tender, surprisingly diaphanous wine, given its 14.5% alcohol. The tannins have remarkable transparency, the fruit is limpid – raspberries, pomegranate, something a little balsamic, a sweet, deep, gentle tang. Like plucking the strings of a zither. Sumac, tomato vine, barberries. So, so silky and so fresh. The acidity has gentle angles, a sweetness, light and glow – it feels like rolling a gem-cut ruby in your mouth.

It’s a wine that has physically, literally and metaphorically crossed borders, history and cultures. It is both ancient and modern, it is Iranian and Armenian, it was made in exile, but it is also a kind of coming home. Just like Rumi’s work, it is a thing of beauty, which has transcended time and place, culture and language. A message of hope in a bottle.

A shipment of Mòläna has just landed in the US (distributed and sold by Storica Wines) and they are working on getting it into the UK market. Everyone, however, will be able to watch the making of this wine in a film called Cup of Salvation made by SOMM TV. It's currently scheduled to show in Boston and NYC in early December (dates here), and it will be available to stream on SOMM TV soon.

Photos of food platters and Keushguerian at table are the author's; the rest are stills from SOMM TV's movie, Cup of Salvation.