‘The bones of the building’, as my friend Danny Meyer once called the options facing an aspiring restaurateur, will determine a great deal about the eventual restaurant. The location of the kitchen; the style of welcome facing the customers as they walk in; the layout of the tables; how and where the rubbish, and the empty wine bottles, will be taken out at the end of every evening service; the lighting; and, most importantly, the effect on labour costs of the building’s layout.

I have encountered this quandary on two very different occasions. The first was back in 1980 when I first saw L’Escargot on Greek Street, a building that was to be my second home for much of the 1980s. I immediately fell in love with the bones of this building, a five-storey 18th-century townhouse, despite the fact that its kitchens were all in the basement and there were countless stairs to negotiate. The higher labour costs that this layout engendered – the servery on the first floor was expensive to man and to operate – were during my tenure at least offset by a friendly arrangement with the landlord.

I saw this predicament unfold a second time when advising Argent on the widely admired redevelopment of King’s Cross. All we had initially to offer potential restaurateurs was in the old Granary Building, which was exposed brick and obviously Victorian. The site eventually occupied by Caravan was 4,000 ft2 (372 m2) on one floor. But the building round the corner from it that was to become the extremely popular Dishoom was completely different. This was on three floors – four by the time the restaurateurs had installed a completely new level complete with kitchen – and would necessitate plenty of fit, young waiting staff.

What was perhaps most interesting was the restaurateurs’ reaction to what they were being shown. At the outset the enthusiasm for what they saw was invariably the same. They did not like the old buildings and only wanted to be shown the newer buildings that were not then available. But once it became clear how popular Granary Square was becoming with visitors of all ages, this attitude changed. ‘We like the new buildings’, came their response, ‘but we would much prefer to be part of an old building.’ But by that time, all the available restaurant sites in the old buildings had been let.

I have recently eaten in three very different restaurants, each of which expressed the charms of old buildings.

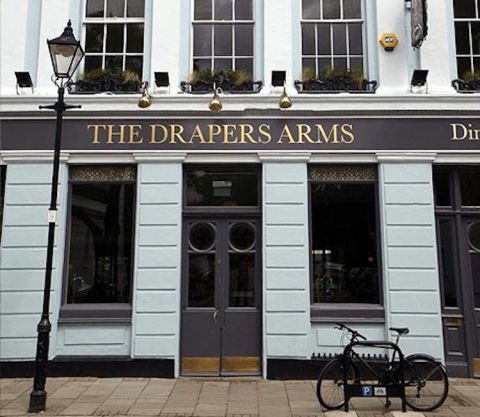

The Drapers Arms is a public house on Barnsbury Street in Islington that was built for the draper and milliner Charles Armstrong in 1899 and today is owned by Nick Gibson. Little has changed since 1899. The entrance leads directly into the wooden-floored bar over a trapdoor through whose gap between the flaps you can rather disconcertingly see the cellar. Once this has been navigated, the welcome is warm and one that attracts a wide range of customers: numerous dog owners, a solitary man in the corner, two couples sharing a large table, and seemingly plenty of regulars. On the way out there is a polite notice asking you to leave quietly as there are neighbours close by.

To the left and the right of the bar there are bare wooden tables and assorted chairs (there is a garden out back) laid up in the evening for the restaurant. And on either side of the bar are bookshelves crammed with paperbacks, an immediate sign that this interior is a well-loved and popular space.

The menu is a single sheet while the wine list is several. We ate well, food produced in a basement kitchen, connected to the back of the bar by the sort of dumb waiter on which we so nervously depended at L’Escargot. I chose the dish of bone marrow and beef-fat toast, with various home-made pickles, followed by a fillet of John Dory swimming on a base of a bisque with mussels, prawns and white sweet potatoes. Jancis chose a dish of scallops with a saffron and orange sauce followed by a Catalan black pudding that was enough, after leaving most of it to be taken home in a doggy bag, to provide lunch for her for the next couple of days. Nevertheless, she helped me polish off a dish simply described as ‘berry pavlova’ that was exceptionally good: crisp meringue, lashings of cream and lots of mixed berries.

The Drapers Arms most obvious attraction is, however, its wine list. This is a six-page document tightly packed with gems: Dagueneau’s Pouilly-Fumé; Riesling from Dönnhoff; Côte Rôtie from Rostaing; and a 1995 Rioja Gran Reserva from Tondonia (£200). We drank with great pleasure a bottle of Crystallum, Peter Max Pinot Noir 2021 that was only £46 despite a very well-known wine website revealing that it currently retails for £30. It was selected from a special South African selection chosen by James Handford MW. My bill came to £135.01 without coffee.

I enjoyed similarly good food at Trattoria Bruto, the restaurant which restaurateur Russell Norman took over from Mark Hix, who opened here in 2008. It’s in Smithfield, one of London’s most historic quarters, and once again the kitchen is located in the basement, down an awkward flight of stairs.

This is not the kind of Italian restaurant that many of us today would immediately think of as typically Italian. It is dark, the lights are heavily shaded, and, apart from the few tables outside, there is little natural light. But it has proved to be an ideal location for Norman to create the Florentine restaurant of his vision, one that owes a great deal to the Italian restaurants of New York in the 1950s.

Hence, the dark nature of the interior, the presence of the red-and-white checked tablecloths, the bottles of Chianti in their fiaschi with their retro straw casing, the Negronis offered at £5, and the small, typewriter-style lettering that is used for its menu and wine list. It is a comforting place, one in which one could easily spend lunch, look up from the table and discover that it is almost time for dinner. Here, by myself and sitting at the bar, I enjoyed a dish of anchovies with toasted St John sourdough, an excellent bollito misto, a glass of Chianti and a macchiato, for £39.

My final meal was the most modern in what is the oldest building. The Coal Office restaurant, a collaboration between designer Tom Dixon and chef Assaf Granit across Granary Square from Caravan, is housed in what was originally known as the Fish and Coal Offices and was built in 1851 originally to house the clerical workers associated with the coal trade, whose produce used to travel on barges along Regent’s Canal, which flows past this tall, narrow building.

Other than the brickwork very little was left of the original. The narrow run of the building has been dealt with by putting in an ultra-modern kitchen along the far wall and filling every available space with tables and chairs. The noise from the open kitchen, the laughter of the waiting staff and the extremely loud music make most of the tables suitable strictly for the under-35s. And it was far too dark for me to take any photographs.

But this, my fifth meal here, was undoubtedly the best, partly, I believe, because they have shortened the menu. A kubalah, a fine example of this soft doughy Jewish/Yemeni bread: an intriguing aubergine tartare; a grilled piece of octopus and yoghurt; and a dish of grilled mushrooms, all of which worked well with a bottle of Chianti Rufina from Selvapiana 2020 (£55). With a couple of excellent desserts, the bill for three came to £226.

In my opinion, whether a restaurant is housed in an old or a modern building is a fact overlooked by most restaurant-goers. Next time you walk in, pause for a moment and have a look around you. The bones of a restaurant, particularly one located in an old building, are invariably well worth looking at.

The Drapers Arms 44 Barnsbury Street, London, N1 1ER; tel: +44 (0)20 7619 0348

Trattoria Brutto 35–37 Greenhill Rents, London EC1M 6BN; tel: +44(0)20 4537 0928

Coal Office 2 Bagley Walk, King’s Cross, London N1C 4PQ; tel: +44 (0)20 3848 6086