It had been 15 years since I’d been to Türkiye to study its wines and much had changed, for good and bad.

In 2009, Turkey, as it was then known, was still feeling the effects of a 1990s renaissance in Turkish wine. Boutique wineries were popping up all over the place, focusing largely on Turkish versions of international grape varieties such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot and Chardonnay.

But President Erdoğan’s regime has been no friend of wine production. Today there are strict controls on where and how wine can be sold. It’s a crime for anyone to mention wine on social media. And since May this year, those who make wine for sale, on however small a scale, have been required by law to set aside millions of Turkish lira in anticipation of likely fines.

The result is that there is a culture of fear of officialdom among the country’s 191 wine producers. Inspectors can turn up at random and make what seem to wine professionals crazy demands. It’s illegal to trade used barrels, for instance.

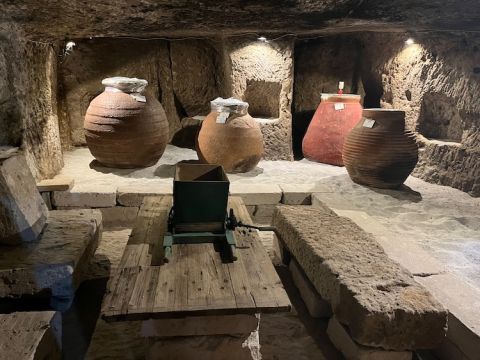

I visited one producer in Cappadocia who shall remain nameless. Like producers all over the world, they make their wine in clay jars, deemed unhygienic by the local inspector, who now comes every month to ensure they still have their lone little stainless-steel tank in which they have to pretend they make their wine. Another Spanish winemaker had to be talked out of returning to his home country, so heavy-handed had been his last inspection.

My wine-writer colleagues Oz Clarke and Caro Maurer MW were due to attend a big wine fair in Istanbul in May but it was cancelled at a moment’s notice when the organiser failed to get permission for an event that would involve actually serving wine.

The Root Origin Soil Conference that I was invited to address last month had been carefully designed not to ruffle any official feathers. The only wine served was a tasting of an array of truly exciting wines made almost exclusively from indigenous grape varieties organised for me alone by a wine-mad Ankara architect Umay Çeviker (pictured with me below), one of four founders of Heritage Vines of Turkey, an organisation devoted to keeping these promising vines in the ground.

In the last four years, Türkiye has lost more vineyard area than New Zealand has in total, with farmers switching to more profitable crops such as apples and nectarines. And there is little respect for old vines, one of the country’s richest wine-related resources because old vines tend to make better wine, and can withstand the vagaries of climate better than young ones.

The 84 wines I’d tasted in Istanbul back in 2009 featured a grand total of six Turkish grape varieties, mainly only as minor components in blends with international varieties. But Çeviker managed to field 31 different Turkish grape specialities in the 64 wines he showed me, and told me that there are now as many as 68 featured in wines in commercial circulation, many of them featuring proudly on the front label as single-variety wines.

The national grapevine collection at Tekirdağ includes at least 854 varieties. Not all of these are wine grapes, however. Despite recent shrinkage, Türkiye still has the world’s fifth biggest area of grapevines and is still the world’s biggest producer of raisins while only 3% of the country’s vines produce grapes destined for wine.

But what wines! There is such a panoply of distinctive flavours and styles, partly thanks to the creativity of the winemakers. I tasted wines made from arboreal vines (grown up trees), wines in concrete, egg-shaped fermentation vessels; wines aged in egg-shaped barrels to encourage the circulation of lees; a rather Riesling-like wine made in oak from the grape responsible for sultanas; a fashionable pet-nat; and a white wine fermented with grape skins left from making red wine.

Thanks to the country’s geography and geopolitics, there are many non-Turkish influences, too. In the east and south, Türkiye borders, in a clockwise direction, Georgia, Armenia, Iran, Iraq and Syria. I tasted a wine grown on the Armenian border at 1,780 m (5,840 ft; higher than any European vineyard); wines made from Georgian, Syrian and Cretan grape varieties; as well as wines from the Kurdish zone that was a no-go area not so long ago.

Then there was the infamous ‘population exchange’ of a century ago when many Greek-speaking Christians were expelled from Türkiye and Turkish-speaking Muslims resident in Greece forcibly relocated to Türkiye. Many of the Greek-speakers were skilled and enthusiastic wine-growers.* Their exodus considerably diminished such wine culture as Türkiye had after centuries of Ottoman rule. It would be no surprise if some of the grape varieties thought to be Turkish turned out to have Greek origins.

Having seen, indeed encouraged, a global increase in the appreciation of Greek wines, with their similar wide range of grapes and terroirs, I would love to see Turkish wine more widely appreciated outside Türkiye. (There’s also a parallel with another wine-producing country that can offer a stimulating range of indigenous wine styles and flavours, Portugal.)

But for the moment, in the US for instance, the offers for ‘Turkey’ on Wine-searcher are dominated by Wild Turkey whiskey. Only a handful of Turkish wines are available in the UK, and even Turkish Master Sommelier Isa Bal, ex Fat Duck and now with his own Michelin-starred restaurant Trivet in London, has remarkably few Turkish producers on his exceptionally eclectic wine list. Turkish wine exports currently represent just 3% of the country’s production, and are worth only £8.5 million, about a tenth as much as a single release from a Bordeaux first growth.

During my speech to the Istanbul gathering of wine lovers, winemakers and wine professionals, the hall erupted into knowing laughter when I suggested that the only way they would make headway exporting their wine was to work together. But when we were all sipping wine beside the Bosphorus at the reception after the conference, Yiannis Paraskevopoulos, another speaker and head of the Greek wine producer Gaia, agreed with me, and added, ‘if we Greeks can co-operate with each other, then surely the Turks can’. He also pointed out that ‘one company managing to sell abroad means nothing. You need a generic body’.

Wines of Greece somehow manages to navigate a path between individual producers and government, but Wines of Turkey has shrivelled to a shadow of what it was between 2008 and 2014. So for the moment it’s probably best to try to find wines from the country’s biggest producers Doluca, Kavaklidere, Kayra, Pamukkale and Sevilen, who are most likely to have taken the trouble to export, and the wines of Paşaeli and Chamlija are also exported.

UK importers of a few Turkish wines are Berkmann (whose Sevilen wines I can heartily recommend), Gama Wines, Graft Wine Co, Hallgarten & Novum, N'Joy Catering, Taste Turkey and The Wine House Warwick.

Best-known Turkish grape varieties

But there are many, many more …

Whites

Emir Mineral, crisp Anatolian

Narince Widely planted friend of oak used for both wine and dolmades

Yapıncak Highly distinctive, recently rescued Thracian

Reds

Boğazkere Traditional blending partner of Öküzgözü, providing structure

Kalecik Karası Lots of sour-cherry flavour from near Ankara; possibly a Hittite legacy

Öküzgözü Provides the juicy fruit for blends with Boğazkere

*Text corrected 16 July 2024 to remove an erroneous reference to Greek and Turkish 'nationals'.

Members of JancisRobinson.com have access to the tasting notes, scores and suggested drinking dates on the 64 wines tasted last month in Turkish wine – flying high. There are a few international stockists on Wine-Searcher.com.