WWC23 – Auntie Yinka, by Farrah Berrou

In this submission to our 2023 wine writing competition, Lebanese wine writer Farrah Berrou writes about moving to the United States and meeting Auntie Yinka, a customer she befriended while working at a wine shop, who became her favourite wine person. For more great wine writing, see our WWC23 guide.

Farrah Berrou writes Farrah Berrou is a wine writer and podcaster based in Beirut, Lebanon. She runs B for Bacchus, a media company that focuses on wine stories from Lebanon and the Eastern Mediterranean. She publishes regularly on her Substack, Aanab News.

Making friends in Los Angeles is rough. I learned that not long after moving there in the Spring of 2021. The layout of the city means that you don’t see people often enough to build the intimacy needed to sustain new relationships. Coming from Beirut, I was used to the idea of running into someone I knew anytime I left the house or being able to down an afternoon coffee with a friend without the need for a Google calendar invite. I thought it was part and parcel of living in a densely populated, tiny city but I now know it is just the Lebanese way of operating. Southern California was a different beast when it came to forming meaningful connections with ease.

I started working part-time at a wine shop in the Valley about 6 months after my arrival. It was my entry into the U.S. wine industry but it also turned out to be one of the few places I and others would return to on a weekly basis. The most unexpected part of being behind the counter, or “in the pit” as the team would begin to call it, was that that was where the majority of my new LA friendships would form. Beyond my two coworkers who became the younger and older brothers I never had, I also got to know the people on the other side of the counter: the weekend regulars.

Three days a week, I was a guest star in the episodes of strangers’ lives as they were in mine. I’d ring up their mixed case of whites and they’d share morsels of their latest adventure or just their random Tuesday. As the store’s de facto Ancient World wine buyer, I had conversations with customers in front of my small section at the back in an effort to explain a region that is glossed over when it comes to typical wine education. What used to start as an overview of Lebanon’s wine regions would shift into discussions on shared family lineages or miniature lectures on geopolitics and history. To carve out an identity that regulars could cling to, I started a weekly dispatch via email where I’d talk about wines from my section but also share pieces of my own curiosity and personal story. I could feel the impact in my inbox but it translated in person too. There were customers, and then there were people I started to know.

There was A, who would come in through the back entrance to fill up two wine bags with Prosecco, Fritz Muller Perlwein Rosa Trocken, Union Sacre Pinot Blanc, and whatever new natural wines we’d brought in. Then, her sister would come in a few hours later through the front and do the same. There was M, who, in response to me telling him how I’d left Lebanon without a solid plan, told me about the time when he too was 34 and lost, with only $600 in his pocket. In the most calming way, he said, “you’ll be okay” and I choked up. There was another M, the guy in the MATH dad hat with an infinity tattoo, who lived in New York but dropped in whenever he was in town visiting his mom. Our banter felt like he was someone I’d known since high school. There was S, the actor who’s in everything, who would always buy a bottle of Honig Cabernet Sauvignon but would only share film fun facts when the store was empty. There was R, who, after I greeted him, simply said, “thanks for remembering my name, it makes me feel special.” There were the other Rs, an older couple who would buy 6 bottles from the bargain zone and a bottle of Knob Creek bourbon every Thursday. There were the Greeks, Lebanese, and Armenians who were all happy to be visible because of the section I commandeered and who would make it a point to say hello to me because we had culture binding us like distant cousins. Give me a letter of the alphabet and I’ll give you a stranger who became a familiar, friendly face and if these regulars weren’t regular, I’d worry about them. I was living alone and anonymous in the suburbs just outside of the LA county line but the shop 30 minutes away became my town square.

And then there was Auntie Yinka who usually came in every other Saturday.

Working as a salesperson in retail can deplete your physical and mental energy. Not all customers are appreciative or kind. There were days when I was socially spent but Auntie Yinka would walk in and shake things up. Her vibrancy would emanate and I’d feel recharged. Her daily staples were Poggio del Moro’s Chianti Colli Senesi Riserva and Marcelo Pelleriti’s Malbec but good Champagne was her true love. With each passing Saturday visit, and much to the chagrin of my disgruntled manager, our conversations at the counter would get longer. She once told me that she bought wines I’d email about, not just because she trusted my taste but because I was the one recommending them.

Her being Nigerian, we bonded over our similar, messy feelings of home being rooted in another (complicated) country. Even after 40 years in the U.S., she could relate to my being protective over a place that others saw through a cracked lens, places that crafted our spirits. We’d talk about family and customs and the void that the lack of community created. We exchanged book titles that unpacked our respective lands; I gave her copies of my self-published newspaper about Lebanese wine culture and she introduced me to Fela Kuti, pioneer of Afrobeat. She invited me to her Boxing Day party because “no one should feel alone during the holidays.” At first, I thought it was a courtesy invite granted out of pity but when she brought her daughters to the shop that December and gave me a Happy Holidays hug in the parking lot, I felt she was genuinely happy to bring me into her world.

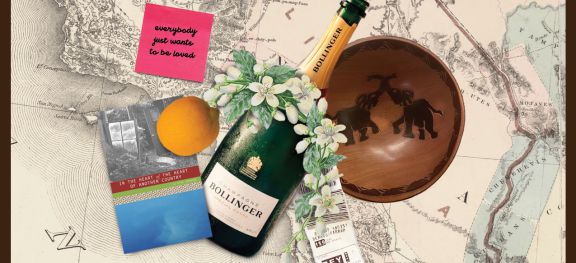

I used to write down things I would hear at the shop. Sometimes they were borderline or outright offensive remarks about the Middle East and sometimes they were tender quotes I wanted to keep as souvenirs of the regulars I never would’ve met without that job. One Saturday, I wrote down, “Everybody just wants to be loved.” It was Auntie Yinka’s first entry into my customer scrapbook made up of a stack of multicolored Post-its.

After a year and a half, I was ready to move on from LA and head back to Lebanon for a while. When I resigned, I sent a goodbye email to my Ancient World mailing list and, despite her feeling under the weather, she came in during my last weekend. She gifted me two African bowls with a pair of elephants on them so that I’d remember her. They now sit on my coffee table in Beirut. In the card that came with them, she wrote, “friendship transcends generations no matter where you find yourself.” She didn’t know it then but I too was putting together a farewell package for her, one that included a delayed copy of Etel Adnan’s In the Heart of the Heart of Another Country, a thin work that I take everywhere with me like it’s a driver’s license. I stashed it in her latest wine order on my last day.

In some ways, I don’t know Auntie Yinka that well but I do know she is a woman who made me feel looked after and understood, I know she is fervently in love with her three kids and is now a grandmother for the first time, and I’d guess her favorite color is red because of the earrings she used to wear. I have had gumbo in her kitchen and I have sliced orange lemons from her garden but ironically, we have never had wine together. And yet, without wine welding our individual timelines into one during my brief stint on the West Coast, we wouldn’t have crossed paths and we wouldn’t have become friends. I’m so grateful we did.

The illustration is the author's own work.

Become a member to view this article and thousands more!

- 15,408 featured articles

- 275,024 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 15,408 featured articles

- 275,024 wine reviews

- Maps from The World Atlas of Wine, 8th edition (RRP £50)

- The Oxford Companion to Wine, 5th edition (RRP £50)

- Members’ forum

- 48-hour preview of all scheduled articles

- Commercial use of our wine reviews