I’ll keep the football analogies to a minimum but the end of the month in which France won the World Cup seems an appropriate moment to reflect on the pluses and minuses of the season so far. For wine growers, or viticulteurs, the business end of the season will soon be upon us.

Following on from a wet winter and a thoroughly damp spring, the start of the summer has been dry and hot. In fact, of the last 44 days, 22 have seen temperatures over 30 °C (86 ºF) around Bordeaux, with another 14 days over 28 °C (82 ºF). July itself has been the hottest in France since 1947, still behind 2006 and 1983 but knocking 2015 into fourth spot.

In that six weeks or so since a largely successful flowering, we had some useful rain at the end of June and start of July, and after that it’s been dry, although some areas had a mid-month downpour. This glorious, sunny patch has been great for the vines, as hydric stress has a way of convincing the vines to concentrate on fruit production rather than on further vegetative growth. Cool nights (around 16 °C/61 ºF) have been good for bunches of young grapes and holidaymakers alike.

The dial will be turned up several notches later this week, however, with daytime temperatures in the mid to high thirties as a heatwave moves up from the south, and we will no doubt see some vines suffer in the burning sun. Younger vines on drier ground are most at risk, and the forecast is for no rain through mid August. (Perhaps we’ll see limited irrigation being permitted, as in the Rhône Valley this summer.) We have a long way to go as the grapes have only just started changing colour (see above right), and there’s a while before the ripening period proper in the run up to harvest, yet too much heat and stress now and the vines can effectively switch off, so we have to hope that the torrid heat will ease off swiftly.

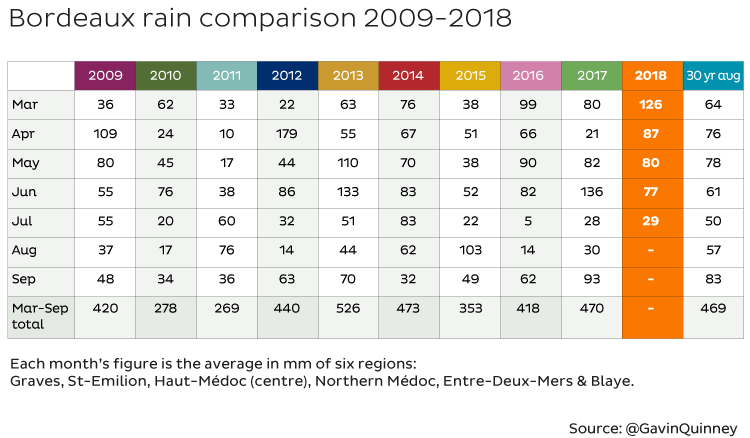

Looking further back to understand the water levels, and for a more complete picture than that provided by my local weather station, I’ve taken the figures from the same six stations I normally use as these are dotted around the main vineyard regions of Bordeaux.

Last autumn was quite dry with October and November 2017 registering 18 mm (0.7 in) and 70 mm (2.75 in) of rain against a 30-year average of 93 mm (3.7 in) and 110 mm (4.3 in) respectively. Then it fairly poured down in the winter. In December 2017, 156 mm (6.1 in) v 106 mm (4.2 in) average, and 155 mm (6.1 in) in January 2018, almost double the average of 87 mm (3.4 in). February rainfall was about average, with 66 mm (2.6 in) v 72 mm (2.8 in) average.

March rain was well above average, so, on top of the winter rain, we might have had plenty of water in reserve but we also had soggy vineyards that were hard to access by tractor for maintenance work and for spraying when the time came. The vines kick into life with bud break in April, and April, May and June saw rainfall at slightly higher levels than the average, but nothing untoward once summer kicked in after mid June. Just look at the comparable months of 2016, and most of us in Bordeaux would be happy if we ended up with a season and the resulting wine like that. That year, I recall, we had a drought from 23 June to 13 September. (Here at Bauduc we’ve had 360 mm/14 in of rain from March to July in 2018, with almost a third of that handily back in March, compared with the combined Bordeaux 2016 figure in the grid of 342 mm/13.5 in.)

This has been the fourth dry July on the trot, though the difference with 2018 is that it’s been much hotter than the last two years – over 2 °C (3.6 ºF) warmer than the average in Bordeaux and indeed 2 °C above 2017. June too was warmer at 20.5 °C (69 ºF) compared with the average of 19.3 °C (34 ºF), May was on a par with the average and April much warmer. These elements were good for vine growth and for the flowering in June, but also for the increased threat of downy mildew in the humid conditions.

Every week, our suppliers would send us a mildew risk assessment as ‘favorable’, meaning, somewhat conversely, that conditions were favourable for the mildew but not for the grower. We’ve had the toughest test against mildew since the dodgy 2013 season and some vineyards have really struggled to keep this fungal disease at bay – it can affect bunches as well as leaves. Our team have done a great job and we’ve had only minimal impact on the red and no mildew at all on the white but I have been fairly surprised to see some pretty well-managed properties really struggle, with mildew clearly evident in the vineyards. The vast majority of top châteaux have coped well in this regard, however, and the vines look verdant and healthy, but mildew has indeed been an issue.

Yields meanwhile look very promising, despite some rain in the first half of June during the flowering.

Others have not been so lucky because in 2018 there have been several storms, often accompanied by hail warnings. Whereas in 2017 a widespread frost at the end of April resulted in a substantial loss for the region as a whole, hailstorms have wreaked havoc on vineyards in a number of really unlucky appellations this year. Following a localised hailstorm in the Médoc on 21 May, the most devastating storm on 26 May took out thousands of hectares in Bourg and Blaye and in the southern end of the Haut-Médoc. It had begun in the northern Graves and ripped through parts of the city of Bordeaux on its journey north towards Cognac. (I covered this in this report at the end of May.)

This month, on Sunday 15 July – the very day that France won the football World Cup – hailstorms battered vineyards in Sauternes, the Haut-Médoc (again), the Côtes de Bourg (again) and to a lesser extent near Fronsac. The vines at châteaux such as de Fargues in Sauternes and La Lagune in the Haut-Médoc took a hell of a beating. For some, it was the second season in a row that disaster struck, after being hit by the late spring frost in 2017.

Losing your crop to hail is the stuff of nightmares and the recent sight of rows upon rows of damaged vines, once again, never fails to fill me with a sense of shock and, of course, pity for the grower.

Let’s hope that’s the end of it for this year because otherwise it’s all looking pretty good. Allez les bleus.