As a backdrop to the en primeur tastings that take place in Bordeaux at the end of March and during the first week of April, I offer a look at the production figures and a few statistics for the 2018 vintage. More than that, it's a fairly in-depth breakdown of how the different appellations contribute to the enormous amount of wine that's made here, and how recent vintages compare.

On the face of it, a year that yielded the same amount of wine as the average for the previous 10 years wouldn't seem to warrant a great deal of scrutiny. As with any vintage, however, the devil is in the detail and none more so than with Bordeaux 2018, when the equivalent of 666 million bottles were made. While it was a glorious year for some growers, which will presumably be borne out by the tastings, for others the size of their crop was the stuff of nightmares.

Ten highlights of Bordeaux 2018 production

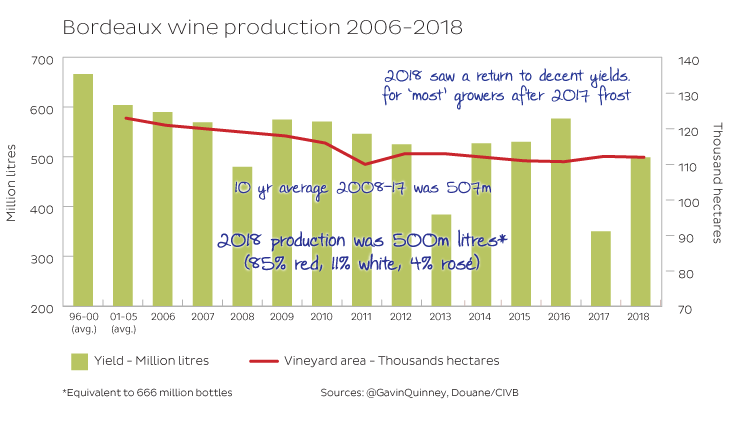

- Bordeaux produced a fraction under 500 million litres in 2018, the equivalent of 666 million bottles.

- Production was in line with the 10-year average of 507 million litres, which itself includes two small crops in 2013 and 2017. In the decade prior to 2013, the average was nearly 570 million litres.

- The vineyard area, at 111,000 hectares (274,290 acres) in 2018, has been consistent in the last eight years, with a consolidation of growers from over 9,000 to under 6,000 in ten years.

- Although an 'average' volume overall, yields from one vineyard to another varied enormously. Some had plentiful crops, while others were hit by downy mildew following the wet spring.

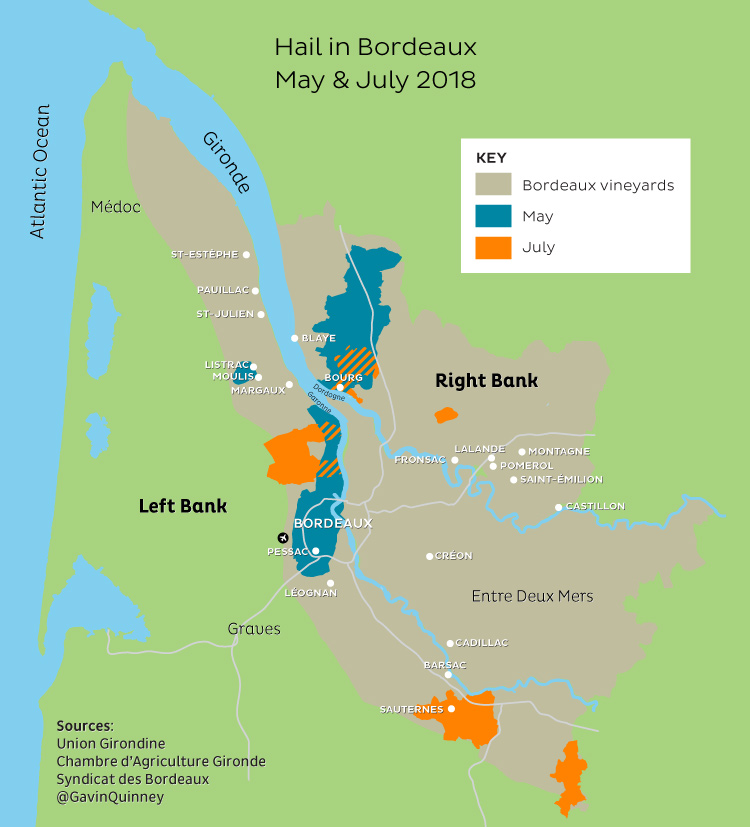

- Hailstorms in May and July caused damage in some unlucky areas.

- Overall, 2018 yields were a vast improvement on the frost-damaged 2017 vintage, though lower than the average of the three vintages prior to that.

- On the right bank, St-Émilion had double the production of the near-disastrous 2017 crop, along with some of their neighbours.

- On the left bank, Pauillac, St-Estèphe and St-Julien (slightly) had lower yields in 2018 than in the previous three vintages.

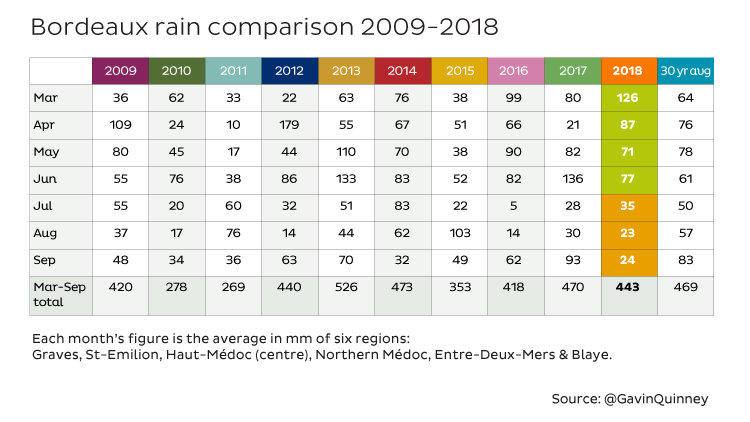

- A wet spring followed by three months of almost uninterrupted sunshine from early July to the first week of October concentrated the grapes.

- 2018 is a vintage that will be remembered with dismay by some châteaux but as one of the greatest by others.

Bordeaux 2018 output compared with that of previous years

Bordeaux produced just under 500 million litres in 2018, close to the 10-year average (2008–2017) of 507 million litres. Today's 10-year average includes the two small 2013 and 2017 harvests while the average production of the 10-year period up to 2013 (2003–2012) was 567 million litres, albeit from Bordeaux's slightly larger vineyard area back then.

This is an updated version of my graphic from my harvest report last October, when I reckoned on a crop of 520 million litres (4% out, dammit).

It's fair to say it's been a rollercoaster ride for Bordeaux growers in the last three years. The 2018 figure of 500 million litres was a welcome return to something close to normal after the frost-damaged 2017, when just 350 million litres were made – the smallest crop since 1991. By contrast, the year before, in 2016, we'd seen an excellent harvest of 577 million litres, which was the largest in a decade. These numbers matter – that drop in production from 2016 to 2017 was the equivalent of no fewer than 300 million bottles.

Vineyard size and consolidation of growers

One often reads about 10,000 growers in Bordeaux and their total of 120,000 hectares (296,500 acres) of vineyards. These figures were true a dozen years ago – in 2007 they were 9,500 and 120,215 respectively – but not today. The size of the Bordeaux vineyard has been pretty stable for the last eight years, after it had been reduced by over 10,000 hectares between 2006 (121,500 ha) and 2011 (110,200 ha). That five-year vineyard reduction programme was intentional, with growers in lesser appellations being offered grants to rip up inferior plots of land. In 2018, the total area was 111,400 hectares (275,275 acres).

What's interesting is that there has been a consolidation of ownership or management of vineyards. A total of 9,044 growers filed a harvest declaration back in 2008, but this figure has dropped steadily and significantly – by 36% – over the last 10 years to 5,834 in 2018. (In 2017, 38% of growers, owning 20% of Bordeaux's vineyard, took their grapes to a co-op, but let's not digress further.)

2018 production split by appellation

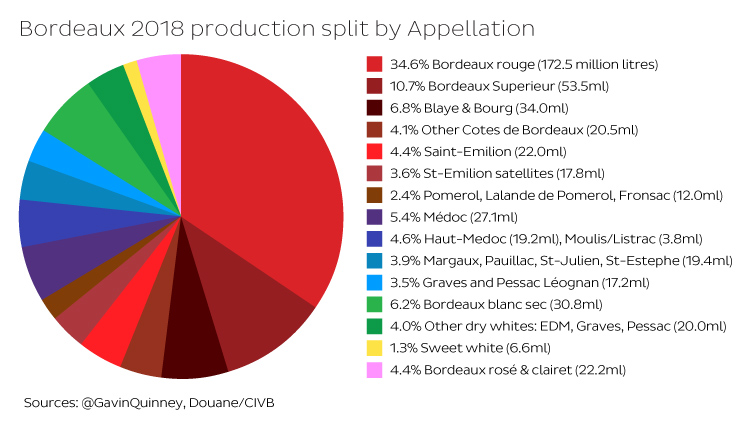

So where do these millions of bottles come from? We often forget, with the hype of the en primeur tastings and subsequent sales campaign, that the top châteaux make up a tiny slice of the cake in volume terms. See this breakdown of the production to show the appellations by group.

Half of the entire production is made up of the generic Bordeaux Rouge, Bordeaux Supérieur and Bordeaux Rosé appellations. These can be made anywhere in Bordeaux though the majority comes from the Entre-Deux-Mers region (even if the label Entre-Deux-Mers is for white wines only). Bordeaux, by the way, is planted with 89% red wine grapes across the board, with two-thirds of that 89% being Merlot. The other third comprises 22% Cabernet Sauvignon, 9% Cabernet Franc, with the last 3% split between Petit Verdot, Malbec and Carmenère.

The widespread Côtes de Bordeaux accounts for 11% of production, and there's a similar amount from what the locals call the 'Libournais' – that's St-Émilion, its satellites such as Montagne-St-Émilion and Lussac-St-Émilion, plus Pomerol, Lalande-de-Pomerol, and the two Fronsacs. Merlot dominates here, of course, with Cabernet Franc in the main supporting role.

Across the Gironde, the four key Médoc appellations of Margaux, Pauillac, St-Julien and St-Estèphe, along with the entire Haut-Médoc, plus Moulis and Listrac, made up just 8% or so of total production in 2018 – about the same as St-Émilion and its satellites. Cabernet Sauvignon is the lead player here, just, though in the whole of the Médoc, which includes the large Médoc appellation to the north of course, there's almost as much Merlot as Cabernet Sauvignon, with the other red varieties accounting for just 6% (source CIVB, 2015).

To the south, the Graves and Pessac-Léognan figure of 3.5% is for red. Their 5 million bottles of white is included in the 'other dry whites' in the chart above. Dry white accounts for 10% of all Bordeaux production – that's still over 50 million litres in 2018, so not to be sniffed at – while sweet white is little over 1%. The white wine vineyards are split between Sauvignon Blanc and Sémillon with 46% each, with Muscadelle on 5%.

Bordeaux yields 2006–2018 by appellation group

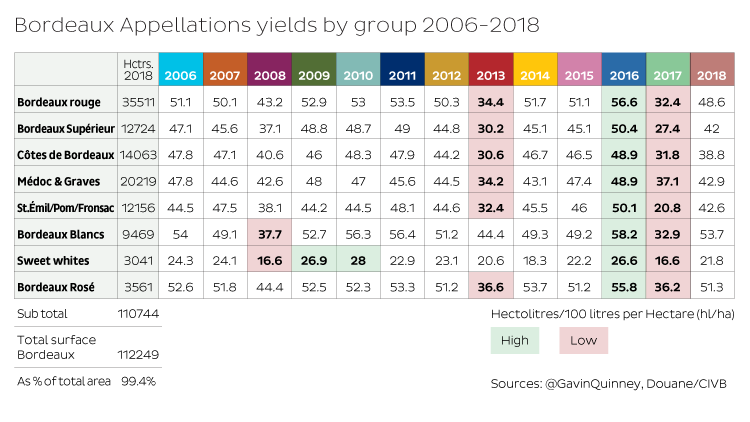

Here's how 2018 compares with previous vintages, in hectolitres of wine per hectare of vines. 2013 and 2017 were the lows and 2016 the high across the board. In any given year, this chart tends to oversimplify things – in 2018, for example, the overall average for Bordeaux Rouge might have been a fairly healthy 48.6 hl/ha but there were huge variations from one vineyard to another. More on the threat of downy mildew later: judging by the huge crop in many vineyards in 2018, it's clear that yields would have been significantly higher had it not been for the presence of downy mildew in the spring and early summer.

Even so, 2018 was a far better result for the vast majority of growers than 2017, when a late April frost nipped the vintage in the bud before the growing season had even begun. Most noticeably, above, after a near-disastrous 2017, St-Émilion and the surrounding areas came back with double the volume in 2018. St-Émilion itself made 22 million litres in 2018, exactly double the 2017 figure of 11 million.

The top Bordeaux appellations

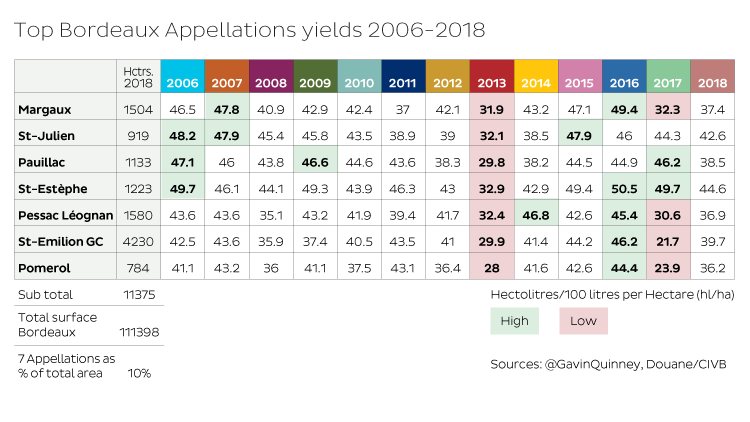

Here is a similar analysis for the best-known and most expensive areas. The vast majority of the wines of interest to buyers (and critics) during the primeurs tastings come from these appellations, with a smattering of others from the Haut-Médoc, Sauternes and so on. These seven areas represent 10% of the whole Bordeaux vineyard, and even then, only a small amount of wines from the large St-Émilion Grand Cru appellation are presented and sold en primeur.

In terms of volume (and this article is all about volume, not quality), there are none of the highs and lows in 2018, compared with the previous five years (though it’s a different story at individual estate level). 2018 was actually a smaller crop in Pauillac, St-Estèphe and, slightly, in St-Julien than in 2015, 2016 and 2017. In Margaux and Pessac-Léognan, 2018 saw a return to moderately good levels after 2017's short crop. St-Émilion and Pomerol saw a lot of frost damage in 2017 so 2018 inched back to normal levels.

The map of Bordeaux 2018 compared with recent years

Bordeaux followers may know where all these places are, but here's a painstakingly laid out map for the many more who don't.

What I've included here are the surface areas of the vineyard appellations across Bordeaux. Note that the vineyards are more or less concentrated in each area. Compare, for example, the 5,500 hectares (13,590 acres) of the northern Médoc appellation, and the similar amount of actual vineyards in the more widespread Blaye appellation.

I've also detailed the yield figures for each area, in brackets, for the 2017 vintage, then the average of the more productive 2014–2015–2016 vintages, and finally the 2018 figure. It's clear from these figures that the northern Médoc suffered far less from the 2017 frost than the vineyards a little further south, and that some of the right-bank appellations saw huge contrasts in fortunes between 2017 and 2018. Lalande-de-Pomerol produced an average of 17 hl/ha in 2017, compared with 43 hl/ha in 2018.

You may want to download a detailed version of this map if you're interested in these stats.

Making sense of yields

Now a note on yields, and how they relate to vines, rules and bottles. All appellations have a maximum yield that growers are allowed to produce, and for 2018 – the limits are always pronounced just before the harvest for some ungodly reason – the maximum for red wines was from 50hl/ha to 60hl/ha, depending on the appellation. It's generally higher for dry whites, though for Pessac-Léognan it's the same for both (54hl/ha). The limits for sweet whites are lower.

The figures refer to hectolitre per hectare, with a hectolitre being 100 litres. In other words, 45 hectolitres per hectare means 4,500 litres (6,000 x 75 cl bottles) from a hectare of vines (100 m x 100 m, or 2.47 acres), which are all in rows. As any visitor to Bordeaux knows, these rows are of varying heights and widths.

The vine density, or number of vines per hectare, changes considerably depending on the area. In the Entre-Deux-Mers and for basic Bordeaux, I'd put the average at around 3,500 vines per hectare. This moves up to an average of around 4,500 in the various Côtes de Bordeaux, while in St-Émilion and Pomerol, the Graves and the Médoc it's more like 7,000 (and higher for the top estates). In the prestigious appellations of the Haut-Médoc such as Pauillac or St-Julien, or in Pessac-Léognan, 10,000 vines a hectare is quite normal for the best estates.

So, for an 'entry-level Bordeaux' vineyard with just 3,500 vines per hectare making 53 hl/ha, that's two bottles per vine. (4,000 is the minimum for new plantations now.) With 6,000 vines per hectare and 45 hl/ha, that's a bottle per vine, while an estate making 38 hl/ha with 10,000 vines a hectare is making around half a bottle per vine.

2018 and the threat of mildew

There's little doubt that Bordeaux would have enjoyed a much bigger harvest had it not been for the damage caused by downy mildew in 2018. Following on from that much smaller 2017 crop, when a late spring frost at the end of April shrank the crop before the growing season had even begun, many growers saw a welcome return to really healthy yields in 2018. (We enjoyed a record crop here at Ch Bauduc in 2018, beating the one set in 2016.)

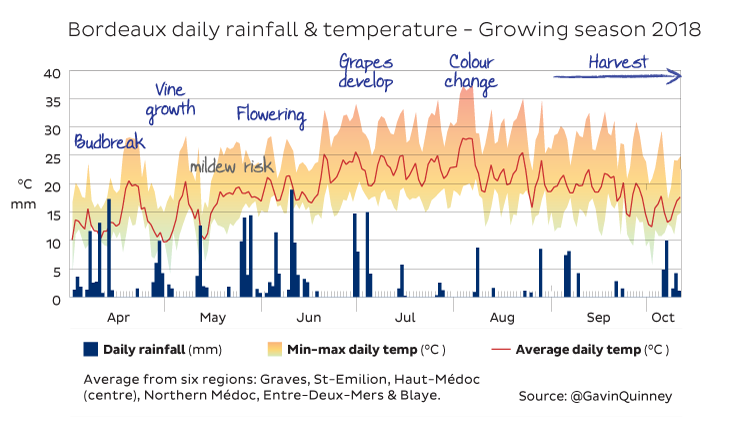

Like 2017, however, fortunes were extremely mixed, with some châteaux enjoying huge crops while others saw their harvest reduced dramatically, particularly by mildew. We're quite used to wet weather in the spring in Bordeaux but the thing about 2018 was the timing of the downpours. Here's my weather chart from my harvest report last October.

We'd had a wet December and January, prior to the wet spring in 2018, although February had seen close to average rainfall. As I wrote in that report, 'the risk of contamination became severe from mid April onwards. The pattern of rainfall in the spring coincided with the spread of mildew unless it was brought under control. Many organic and biodynamic vineyards were hit badly and those conventionally farmed vineyards that missed vital sprayings also suffered considerable losses. A day or two late, in some cases, was to prove expensive – mildew can affect bunches as well as the canopy. As much as a third of Bordeaux vineyards were impacted by mildew to a greater or lesser extent'.

Our vineyard consultant, who advises over 150 vineyards, reckons his clients had to treat the vines on two to three more occasions than usual in the 2018 growing season, with an average of 17 or 18 times for the organically farmed vineyards and 12 times for those using classic, systemic treatments.

Several famous estates that have been switched to organic or biodynamic viticulture, such as in Pauillac and Margaux, saw dramatically low yields, while some less famous areas also had considerable losses due to the impact of mildew. Castillon, for example, although well up on 2017, had yields of only 33 hl/ha in 2018, compared with the average of 44 hl/ha in 2014–2016.

May and July hailstorms

On top of the impact of downy mildew in certain vineyards, there were also some localised hailstorms in May and July 2018 that damaged the crop in some areas.

On 26 May, a storm moved up from south of Bordeaux, up through the city, and on towards the southern end of the Haut-Médoc, before causing significant damage in the vineyards of Bourg and Blaye. 'Pebble-sized hailstones destroy vineyards in Bordeaux', wrote the Daily Mail. 'Hailstones "the size of pigeon eggs" devastate Bordeaux vineyards', said the Telegraph. 'Bordeaux vineyards face bankruptcy after hailstorm', was how The Times put it. A total of 3,000 ha of Bourg and Blaye were affected, some vineyards very seriously. Despite these images of devastation, both appellations managed a creditable 37 hl/ha and 40 hl/ha respectively, against a maximum permitted yield in 2018 of 52 hl/ha.

On 15 July, more hailstorms damaged vineyards in Sauternes and, again, the southern end of the Haut-Médoc.

The game of two halves

But let's not be too downbeat, because we have an outstanding vintage on our hands. At the end of July, I wrote an update on the growing season called 'a game of two halves', partly out of respect for France winning the football World Cup that month, but also because the rainy period was well and truly over. From the start of the knockout stages of the Cup, in early July, it remained dry and sunny. And it stayed that way for three months, all the way through to the harvest.

Here too are the monthly temperatures with the 2018 average of the six regions mentioned in the rainfall chart above, followed by the 30-year Bordeaux average in brackets.

March 9 °C (10.2 °C)

April 13.8 °C (12.4 °C)

May 16.1 °C (16.1°C)

June 20.3 °C (19.3 °C)

July 22.5 °C (21.3 °C)

August 22.1 °C (21.4 °C)

September 19.2 °C (18.5 °C)

June, July, August and September were all considerably warmer in 2018 than the average.

It's fairly common, once the vines have flowered in late May or June and the grapes are forming at the start of the summer, to have two successive months of fine weather. But three is unusual – in 2010 it was also dry in July, August and September. There are similarities too between 2016 and 2018, with a fairly wet first half of the season, then a dry summer and harvest, but in 2016 we had a noticeable change in temperature from 13 September onwards. In 2018, the sunshine just kept on going. 'I cannot recall such a consistently sunny three-month period at the end of the season like this – 2010 came quite close – nor such a stress-free harvest time in Bordeaux', I wrote in my harvest report.

The harvest took place in almost ideal conditions, with no risk of rot. It stretched from around 21 August for the first of the dry whites, well into October for Sauternes and the later-ripening Cabernets. The busiest period for harvesting the reds was during the second half of September and the first week of October. The continued drought had an impact on the volume, as the berries were thick-skinned and were in no way diluted by any harvest rain. The quality, though, was extremely high. And that's what really matters.